No name

Sample Pages from [em]American Cardinal Readers: Primer[/em]

Sample Pages from [em]Andries[/em] by Hilda Van Stockum

The Little House and the Big House

IT WAS EARLY spring, one of those gentle Dutch springs when the air seems to whisper of wonders to come while the earth still lies under winter�s spell. The trees around the Big House, near the village of Lisse, were still bare though the buds were swelling. They were old trees, as old as the House with its ivy-clad walls and proud windows. It was a house that had seen better days, days when ladies with white parasols strolled in the carefully trimmed gardens and little children with striped stockings in high, buttoned boots whipped their hoops around the flower-beds. Now the huge gardens were deserted and no laughter sounded under the trees. No swings danced in the wind, no balls hid in the grass, no tin soldiers marched up and down the gray stone stoops. A tired family had ceased to grow, and for years now the only occupants of the Big House were an elderly bulb-farmer and his fat, lazy cook.

Of course the House was too proud to admit that anything was wrong. It wrapped itself closer in its cloak of ivy and lived over again the lovely golden days of the past. In summer, when the cook drew the blinds over the windows and the trees screened off the world with their leaves, it was easy to pretend that all was as it used to be. But when winter stripped the trees and peeled the window-eyes the Big House was forced to look straight at the little house, which had sprung up like a mushroom on the opposite side of the road, a messenger of change. At one time the road and all the lands across it had belonged to the Big House. In those days it was still a mansion; now it had become a farm, and impudent little houses were allowed to stick up their pert little chimneys and stare at it. Not that the little house was unfriendly; it was a cheerful enough little thing, though terribly common. It had a bright red roof and whitewashed walls, and in summer its little yard was full of flowers and blossoming trees. There were plenty of children running in and out of it, leaving their toys and playthings about, and above its low door hung a gilded wooden shoe, for it was the home of the village�s wooden-shoe maker. Such a thing for the Big House to gaze upon! And if only it had shown a proper respect for its august neighbor, but not a bit of it. It didn�t seem to care in the least what the Big House thought of it, but went on waving its line of clean diapers every other day as if it were the best manners in the world.

But what bothered the Big House most of all was the sounds that came blowing across the road all day, sounds of children laughing and crying and the pitter-patter of little wooden shoes. Those had a way of waking memories the Big House had long believed dead. Every scratch and nick made by children years ago seemed to smart again; a high chair, hidden in the attic under a lot of rubbish, would begin to ache all over and the sofa in the sitting-room would start to creak and throw up dust. In those moments the Big House faced the truth. What it missed was not so much past grandeur with its footmen and its fuss, but the children, just the children. And in its bitter loneliness it would hate the little house that was so bursting full with what the Big House lacked.

Mr. Verbeek, the present owner of the Big House, suspected nothing of all this. He was one of those people who didn�t believe houses could have, or ought to have, feelings. Besides, he wouldn�t have understood them even if he had known they were there. His own childhood was so far away he had forgotten all about it, and he didn�t like children. He always chased them away when he saw them on his fields. He was a quiet, dignified man who was interested in his bulbs and his books and wanted to be left in peace. He didn�t really care much for Cornelia, the cook, who was lazy and much too free with her tongue, but he disliked change so much that he�d rather keep her than try somebody else. There was no chance at all that he would ever marry, and so the Big House thought that it would have to give up all hope of feeling a child�s footsteps on its stairs again.

Perhaps houses can say prayers, like people. Or perhaps, when Saint Nicholas visits the chimneys they, too, are allowed to wish for something. At any rate, the day came when the miracle happened and the Big House�s secret desire was to be fulfilled. The old writing-desk knew about it first and told it to the arm-chair, which whispered it to the grandfather clock. Soon the whole House was filled with the news and a shiver went through it from cellar to attic, where a mirror, which had been balancing for years on an old rocking-chair, fell to the ground with a crash. It wasn�t a secret very long, for as soon as Cornelia heard about it the House resounded with her protests.

"Silly nonsense," the kitchen pans heard her mutter as she smashed the dishes in her anger. "What call has he to bring a child here? An orphanage is where it belongs. It�ll only upset the whole place. Duty? What duty has he to a sister who quarreled with him to marry a common zoo-keeper? What if they did die and leave a child? It happens hundreds of times and that�s what orphanages are for. I�ll give notice. It�s either the child or me. I won�t stand for it." But she never gave notice; she was too well off and she knew it. She dusted the passages and opened new rooms and changed some furniture. She grumbled as she did it and let the food burn in the oven.

"Well, I had so much extra work with this here boy expected," she said when Mr. Verbeek complained. "It�ll be worse when he comes," she added darkly. "You don�t know children."

Mr. Verbeek sighed. He didn�t want to change his peaceful, settled ways, but he had loved his sister dearly before he quarreled with her, and her death had come as a great shock to him. He could not refuse her last wish, and besides, even if she hadn�t asked him to look after her son, he would have found it hard to send his own nephew to an orphan asylum when his house was full of empty rooms. For though not a friendly man, Mr. Verbeek had at bottom a very good heart. So he answered Cornelia firmly.

"It is my duty and I wish to hear no more about it. If the work is too much for you we�ll get extra help. Meanwhile, have the place ready. I�m fetching the boy tonight."

"Did you hear that?" murmured the old table excitedly. "Tonight! Better times will begin tonight!"

"Or worse," grumbled the grandfather clock, who was always a pessimist. But the Big House paid no attention to his remark. It looked upon the little house for the first time without a qualm. "We, too, shall have a child," sang the smoke as it curled from the chimney. "We, too, have a future," rustled the ivy leaves. "We, too, shall be filled again with merry noises," murmured the old walls. But the little house was not in the least impressed. It never paid any attention to the Big House, which it considered an old bore. Nothing ever happened over there, anyway. And just as we take certain pictures on the wall for granted and never look at them, so the little house had long ago forgotten the existence of the Big House, though it loomed so large and dignified behind the bare old trees. For the little house the whole world was wrapped up in the wooden-shoe maker�s family. They were the most important people in Holland, from the bearded father to the dimpled baby. And since they were a healthy and vigorous family, full of conflicting wishes and tempers, the little house resounded with tears and rejoicings in swift succession every day. Therefore, while the Big House was trembling with excitement over the Great Event of its life, the little house was sympathizing with Mother Dykstra, the shoemaker�s wife, who had dinner all ready, with Father grumbling impatiently in his beard, and "those girls" not home yet.

"We�ll have to begin without them," she sighed. "Whatever can have happened to them?" As a matter of fact, at that moment "those girls" were running for their lives. They had ventured into Mr. Verbeek�s bulb-fields to see if there were any signs yet of flowers to come. The winter was so long, they could hardly wait for the first buds to open. But Mr. Verbeek had his big dog trained to chase out little intruders and that fierce creature soon had the girls flying for safety. Mother was just putting the potatoes on the table when they tumbled into the kitchen, their hair blowing about, their hands and knees grubby, their aprons torn.

"Mercy me, what happened to you?" gasped Mother.

"It was that old dog," panted Helga, brushing a golden strand of hair out of her face. She was a sturdy maiden of seven, with sparkling gray eyes and healthy pink cheeks in a round, childish face.

"Yes, and he wouldn�t even let us look at the flowers and I think I saw one that was just going to open�it had yellow inside�and then he came with his horrible face and great big noisy teeth," explained Miebeth, who was only five and as slim and dainty as Helga was sturdy and strong. Her eyes were large, of a velvety brown, shaded by long, black lashes. They were so soft and dreamy you never quite knew if she was looking at you or at a picture in her own mind. Her hair was lighter and more wispy than Helga�s and curled into two little shrimps of wheat-colored braids at the nape of her neck.

"Well, I�m glad you�re back," said Mother. "We were just going to start without you. But first wash, please, you�re a sight!" The girls went outside again to the pump in the yard, one swinging the creaking handle while the other rinsed her face and hands in the cool jets of water. Then they came back and stood at the table. There were chairs only for Father and Mother, there wasn�t much money in this family to spend on furniture, and besides, chairs were wasted on children, who�d just as soon be on their feet. Treeske, the baby, sat on Mother�s lap, ignorant of the beautiful high chair that was pining in the attic of the Big House for the feel of two chubby baby legs, exactly the kind of legs Treeske had, with a dimple on each knee.

The three older children stood with their forks in their hands, ready to pounce on the food, while Father opened the old leather Bible and read:

"Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith. Amen." Scarcely had he shut the book when the forks flashed across the table and each child pricked a potato from the dish, dipped it into the bowl with gravy, and popped it into his mouth.

Little Kobus had to stand on a footstool to be able to reach the food. He was only three years old and couldn�t keep up with his older sisters. He had a round little body and a round little face in which two round blue eyes gazed anxiously at the hill of potatoes that was growing smaller and smaller as the forks twinkled. He tried to swallow a potato whole but he wasn�t quite round enough for that and it stuck in his throat. If his father hadn�t grabbed him and slapped his back until the potato flew out he might have choked. But the others all went on calmly with their dinner. They were used to Kobus. Every day he narrowly escaped death in one form or another and his family accepted it as part of his character.

"I hear we�re going to get a new little neighbor," said Father when he had saved Kobus�s life. "It seems Mr. Verbeek is adopting his sister�s son."

"For pity�s sake," sighed Mother, pressing Treeske a little closer and praying secretly that she might never have to leave her children to the mercy of anyone as dour-looking as Mr. Verbeek. "Who�ll care for him then? A man can�t know about children."

"The cook, I suppose," said Father, quirking an eyebrow.

"That fat creature," Mother cried with a snort. "She is too lazy to look after herself, let alone a child."

"Maybe she�ll get thin," suggested Father humorously.

"Poor boy," muttered Mother, shaking her head. "Not that I think it isn�t right for Mr. Verbeek to take him. But it does seem a hollow kind of a place for a youngster."

Helga had listened round-eyed.

"I wish it was a girl," she said. "Boys are no use." And she pricked the last potato out of the dish.

"That was mine," cried Kobus. "I never get anything."

"Yes, you do, you had five, I counted them," argued Helga.

Kobus began to weep.

"Muvver, Muvver, where�s my appletite?" he wailed. "You pomised me an appletite, you did. Now where is it?"

Mother had to laugh.

"No, son, I only said that if you kept your hand out of the sugar-pot you�d have an appetite for your dinner."

"Well, where is it?" asked Kobus, and seeing the others laugh at him he grabbed the dish of gravy and ran off with it. "If you won�t give me my appletite I�ll drink all your gravy up, so there!" he cried furiously. Mother plucked him back by his shirt, took the dish, and put it out of his reach. Kobus howled, Helga jeered, Miebeth yelled, and Treeske crowed. Mother clapped her hands.

"Be quiet this minute or you all go to bed!" Dead silence. Even Treeske was so astonished at the sudden cessation of noise that she made an O with her lips and kept still.

"Heh," sighed Mother.

"Thank goodness," said Father, pushing back his chair and getting up. "Helga, you come to the shop with me, I have some shoes for you to deliver." Helga followed her father into the front room of the house, where shavings curled around her stockinged feet. Father took a bunch of wooden shoes from a nail in the wall. They were tied together with cords that ran through holes in the sides.

"Three pairs for the Burgomaster�s children, one for Mrs. Pietersen," Father explained. Helga shouldered the load, thinking to herself that she would first go to the Burgomaster�s house, for the Burgomaster�s wife had a pot with lovely cookies which she gave to small messengers.

"Wait, Helga, I�m coming with you!" cried Miebeth.

"Me too!" yelled Kobus, but Mother grabbed him by his pants.

"Lemme go! Lemme go!" he shouted.

"Not you, Mister, you�ve got to go to bed soon."

Kobus began to cry.

"I never may do anything," he sobbed, rubbing his fists into his eyes. Mother pitied him. Holding Treeske under one arm she reached with the other for the sugar-pot on the shelf and fished out a lump which she shoved in Kobus�s mouth. "There, that�s for a good boy," she said. Kobus�s face spread in a grin. With the tears still hot on his cheeks he lost himself in a rapture of sweetness. But much as he loved his sugar-plum he took it out of his mouth once to say warmly:

"You�re nice, Muvver!" after which he was silently happy for a long time.

Meanwhile the girls had followed the dirt road which meandered between pasture-lands and bulb-fields until it changed into a street paved with bricks of many colors with little houses to the right and left of it. Soon this opened up into a cobbled square, at the corner of which stood the dignified old Burgomaster�s house with its gray stone stoop. The children climbed its steps and pulled the brass bell-knob, shaped like a lion�s head. Hendrik, the Burgomaster�s five-year-old son, opened the door.

"Oh, there are the shoes!" he cried. "Which are mine?" and putting the three pairs on the floor he tried them in turn. When he had found his own pair he put them on, stamping up and down the tiled floor of the hall. He liked to imitate his stout father�s air of importance.

"They are only play-shoes," he told Helga, "in case the garden is muddy. I have leather shoes too."

"Huh," said Helga scornfully. "We wouldn�t want leather shoes, would we, Miebeth? Father makes all our shoes and they make much more noise than those dumb leather ones. Listen." And she and Miebeth beat a tattoo with their clogs on the Burgomaster�s stone stoop.

"I can do that too," said the boy, but the heavy shoes were unfamiliar to his feet and when he tried to lash out his legs like Helga he fell on his bottom. The girls laughed merrily. Hendrik scrambled up and stuck out his tongue to show the girls how he despised them. Helga was on the point of telling him what she thought of him when the Burgomaster�s wife came with the cookies.

"Here you are," she said, giving Helga and Miebeth each one. "Go inside, Hendrik, it�s time for your bath." The girls said, "Thank you" politely and then scowled at Hendrik, who was pulling faces at them from behind his mother�s back.

"That boy has very bad manners," remarked Helga sedately when the girls were on their way to Mrs. Pietersen, who lived in a narrow little street on the other side of the square. "I�m sure Mother wouldn�t want us to play with him, so don�t you do it, hear, Miebeth? Wipe that hair out of your eyes, you look awful. Wait, I�ll fix it." Helga fiddled for a moment with Miebeth�s rebellious wisps.

"Aren�t those cookies derlicious?" mumbled Miebeth, slowly nibbling at hers. "I wish Mother could taste this."

"You should keep a piece for her," advised Helga.

"Did you?" asked Miebeth.

"N-no, I ate mine all up," confessed Helga, blushing a little. "But your piece will do for both of us."

"Oh," said Miebeth, looking down dolefully at the beautiful morsel with the cherry on it that she had left till the last. They had by now reached Mrs. Pietersen�s store, a little "thread and tape shop," as it is called in Holland, where sewing materials, paper, and other small articles are for sale. It wasn�t closed yet. This was before the days of early closing, and the lamps were lit because of the gathering twilight. With a tinkle the door let the children in. Mrs. Pietersen was busy helping a customer match some knitting-wool. Meanwhile she was chatting about the latest news.

"I think this will do nicely, Miss Kolf," she was saying. "Yes, I pity the poor boy, losing his mother and father in one blow, so to speak. They say it was one of those new-fangled cars that ran over them. Automobiles, they call �em. They�re a real danger. I hope the Burgomaster will keep �em out of this village, at least."

"They say they�re all the rage in the city, but you can�t depend on them as you can on a horse," agreed Miss Kolf. "Well, it�s a sad thing for the boy. I hope Piet Verbeek is kind to him, I somehow can�t think of him as a mother. You could have knocked me down when I heard he was taking a child into his house. I thought he hated children."

"What chance had he ever to like them?" asked Mrs. Pietersen. "He never came close enough to one to say boo. I know what I�m talking about. I reared ten of �em, and it�s only when you�re up to your neck in work and worry over them that you learn to appreciate them properly. One hank of salmon pink then, Miss Kolf?"

"No, give me two. I don�t want to run short again. How much is that, Mrs. Pietersen?"

"Fifty cents," said Mrs. Pietersen, rolling the wool in tissue paper. "I hear the boy is arriving tonight."

"Well, I hope he�ll work out all right," said Miss Kolf. "Five, ten, fifty, here you are."

"Thank you, and mind your step," said Mrs. Pietersen as Miss Kolf groped her way out into the blue twilight. Mrs. Pietersen now turned her rosy face to the girls. The lamp behind her made a halo of her white hair.

"Oh, the shoes," she said, rummaging in a drawer.

"Mrs. Pietersen," said Helga, "you didn�t tell the truth, did she, Miebeth?" Miebeth shook her head.

"The truth?" asked Mrs. Pietersen. "Aren�t they the shoes?"

"Oh, yes, but you said that Mr. Verbeek never came near enough to a child to say boo and he has often said boo to us, hasn�t he, Miebeth?"

"It sounded like boo," agreed Miebeth. "And his dog says it too."

Mrs. Pietersen laughed heartily.

"It was only a figure of speech," she explained. "Here is the money for your father." Helga accepted the envelope with coins and pinned it carefully in her pocket. Meanwhile Mrs. Pietersen good-naturedly took two shop-soiled picture postcards from a stand. "One for each."

"Oh, thank you," cried the girls, skipping gaily out of the store. By the light of the window outside they examined the pictures.

"What did you get?" asked Helga.

"Sheep," said Miebeth. "Lots of sheep and a church. Let me see yours. Oh, Helga, yours is sweet!" For Helga�s picture had glossy forget-me-nots with hearts and leaves of gold. "Oh, yours is the nicest, I wish I had this one!"

"All right, I�ll change with you if you�ll give me the rest of your cooky," bargained Helga.

"But that�s for Mother," protested Miebeth. "You said so yourself!"

"Half of half of half of a cooky!" cried Helga scornfully. "Grown-ups are so big, they couldn�t even taste such a small piece. And your hands are dirty. Mother wouldn�t even want it. All right, then, you mayn�t have my picture." And she made a grab for it. Miebeth hastily handed her the cooky instead. Then, with a sigh of relief, she bent her head over her forget-me-nots.

"Come on, it�s time to go home, it�s getting very dark," urged Helga, swallowing her cooky in one gulp. "Come, Miebeth," and she dragged her absorbed sister with her. Soon they had left the village and were on the way home. A new moon, like the paring of a baby�s nail, stood shyly in the fading sky, and fields and trees were blurred by the black wing of night. Suddenly a carriage rolled past with a clatter of horses� hooves and a grinding of wheels over a pebbly road. The girls saw the outline of Mr. Verbeek�s square shoulders and beside him the slender, dusky shape of a boy. Helga pinched Miebeth�s arm.

"Look, look," she cried. "It�s Mr. Verbeek�s boy, he has come!"

"Oh," said Miebeth, gazing after the dwindling carriage with pensive eyes. "I�m sorry for him."

"Why?" asked Helga.

"Because he has to live forever and ever with Mr. Verbeek and that horrible dog!" said Miebeth. The girls both shuddered. Then Helga pointed at two merry squares of light that twinkled between the trees ahead. "Look," she cried. "Mother has lit the lamps, we�ll have to run!" and taking each other by the hand the girls galloped home.

Sample Pages from [em]Archimedes and the Door of Science[/em] by Jeanne Bendick

Who Was Archimedes?

ARCHIMEDES was a citizen of Greece. He was born in 287 B.C. in a city called Syracuse, on the island of Sicily.

When Archimedes was born, an olive branch was hung on the doorpost of the house to announce to all of Syracuse that Phidias the astronomer had a son. A slave dipped the baby in warm water and oil and then wrapped him in a woolen band, from his neck to his feet, like an Indian papoose.

The birth of Archimedes was celebrated by two family festivals. When he was five days old, his nurse, carrying the tightly wrapped baby in her arms, ran round the circular hearth in the main living room of the house, with all the other members of the household, both the family and the slaves, running behind her. This ceremony put the baby forever under the care and protection of the family gods.

The tenth day after he was born was Archimedes' name day. Phidias had a party for all the family and their friends. In front of all the guests he solemnly promised to bring up his son and to educate him as a citizen of Greece. Then he gave the baby his name - Archimedes.

It was just a single name, without a first or last one. Maybe Archimedes was named after his grandfather, Ior a friend of the family, or a god. Much thought went into giving the baby a name, which was carefully chosen to bring him luck. Then the guests piled their presents near the swinging cradle, a sacrifice was offered to the gods, and finally a great feast was served.

The family gods must have looked kindly on the baby Archimedes, and his name must have been well chosen, for he grew up to be one of the greatest scientists the world has ever had. Most of the things you know about science would have dazzled and bewildered him. But many of the things you know about science began with Archimedes.

What was so unusual about a man who spent almost his whole life on one small island, more than two thousand years ago?

Many things about Archimedes were unusual. His mind was never still, but was always searching for something that could be added to the sum of things that were known in the world. No fact was unimportant; no problem was dull. Archimedes worked not only in his mind, but he also performed scientific experiments to gain knowledge and prove his ideas. Many of his ideas and discoveries were new. They were not based on things that other people before him had found out.

Imagine what this means.

Nowadays we do not have to think about most things from the beginning, because we have the knowledge of all the things that men have leamed over thousands of years.

The great mathematicians of modem times have the knowledge and the proofs of thousands of other mathematicians to help them. The greatest scientific discoveries are based on things other scientists have leamed, bit by bit.

A famous scientist once said that he was able to see so far because he stood on the shoulders of giants. Archimedes was one of the giants. He was one of the first.

The scientists who came after him had more and more to work with. Archimedes had only the principles - the basic ideas - of the great mathematics teacher, Euclid, and these ideas - that a straight line is the shortest distance between two points, and that the next shortest distance is a shallow curve, and that each deeper curve is longer.

That's not much! But the mind of Archimedes - that curious, logical, wonderful, exploring mind - made up for the things people before him had not found out.

Archimedes began the science of mechanics, which deals with the actions of forces on things -

solid things, like stones and people,

liquid things, like water,

gases, like air or clouds.

He began the science of hydrostatics, which deals with the pressure of liquids.

He discovered the laws of the lever and pulleys, which led to machines that could move heavy loads, or increase speeds, or change directions.

He discovered the principle of buoyancy, which tells us why some things float and some things sink and some things rise into the air.

He discovered the principle of specific gravity, which is one of the basic scientific tests of all the elements.

An element is a basic substance. There are no combinations of substances in an element. Gold is an element, and so is silver, and so is lead.

The gas, hydrogen, is an element, and so is oxygen. But if you combine them together you get water, which is not an element, but a compound.

Archimedes discovered that every element, and even every combination of elements, has a different density, or weight for its size -and that this is a good way to tell one substance from another, even if they look alike. The density of any substance, compared with the density of an equal amount of water, is its specific gravity.

He invented the Archimedean screw, a device that is still used to drain or irrigate fields and load grain and run high-speed machines.

He invented a kind of astronomical machine that showed eclipses of the sun and moon. He estimated the length of the year, and the distances to the five planets that were known to the ancient world. For three years his war machines defended the city of Syracuse against a great Roman fleet and army. But although he was a great inventor he con- sidered inventing an amusement, and mathematics his real work.

Archimedes wrote brilliantly on almost every mathematical subject except algebra, which was unknown to the Greeks. (You can't have algebra without the idea of zero, and no one thought of zero until hundreds of years after Archimedes lived.) Some of Archimedes'mathematical theories were so complicated that even today they can be understood only by experts.

He was the first to show that numbers unimaginably big, bigger than all the things there are, could I be written and used.

He lit the flame that led to the invention of the calculus, which is the mathematics of changing rates and speeds and quantities.

The door to modern science opened through the mind of Archimedes.

But probably the most important thing Archimedes gave to the world was a logical way of thinking about mathematics. Like his predecessor, Euclid, he had a way of taking things in order, step by step, so that he could prove or disprove his ideas as he went along.

Archimedes lived in one of the greatest civilizations the world has ever known, among many brilliant minds, and yet he was outstanding even there.

What was the world of Archimedes like?

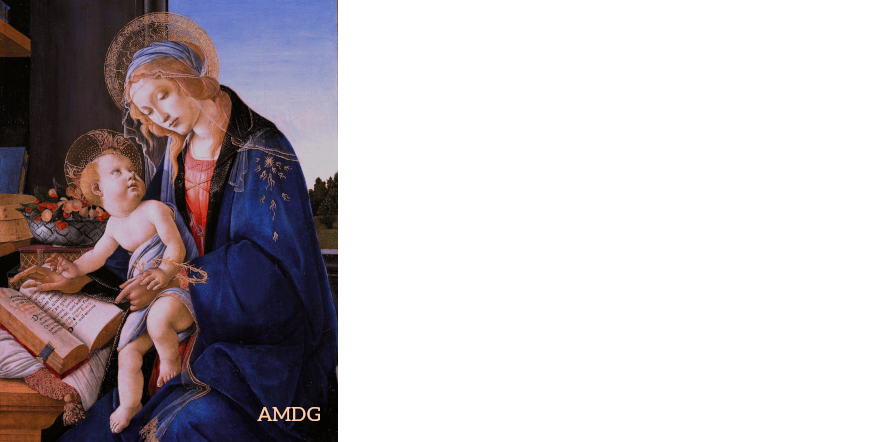

Sample Pages from [em]Art Through Faith[/em] by Mary Lynch

Sample Pages from [em]Beany Malone[/em] by Lenora Mattingly Weber

This windy Saturday in October had started with such a gusty happiness. But then all Saturdays in the big Malone home were a hectic, happy hullabaloo with young folks coming and going, with bath water running, with someone standing at the top of the stairs yelling to someone in the kitchen, with the telephone in the back hall ringing - forever ringing.

Sixteen-year-old Catherine Cecelia Malone - known as Beany to family and friends - had started the day with nothing more weighty on her mind than whether they should make chocolate or peppermint-stick ice cream for the party she was putting on this afternoon (and whether the freckle cream she was secretly buying at the drugstore would dim the marching formation of freckles across her nose). She had no idea that she would be a different Beany by the time the day ended. She had no idea that the Malone way which had seemed so right that morning would seem to wrong by nightfall.

Beany was in the kitchen now, making seven-minute icing for the cake her older brother Johnny was watching int he oven. The cake had been delayed by Johnny's frequent dashes to the telephone. On the kitchen table, the drainboards, even the stove's top, was the floury spilled-sugar, egg-shell clutter that always accompanied this creative feat of Johnny's

The sprinkling of freckles across Beany's nose was almost lost int he warm flush of her square-chinned face as she vigorously wihpped the icing in the double boiler. Her stubby brown braids, which she wore pinned up now that she was a high-school sophomore, kept higgling time the egg beater. "They o ught to call this seventeen-minute icing." she grumbled with her eye on the clock, which said five after one; and the party was to be at two.

At first Johnny's Lady Eleanor cake had soared to such beautiful heights. "Look at that," Johnny bragged with the oven door open a crack. "It takes creative genius to make a cake like that. Light as a snowflake in spring."

"It takes fifteen egg whites," Beany reminded him practically.

But on the next peek Lady Eleanor wasn't doing so well. She was falling in the middle, and about that Johnny waxed philosophical. "Just like life. Your hopes lift so high and then somehow there comes a sag...Beany, do you suppose you could fill in that depression with icing?"

"Oh sure," Beany said.

Johnny pulled out a broom straw to test it. Johnny was eighteen. He was tall and thin, with a light-footed grace and a shock of curly black hair. Beany, the most practical of all the Malones, was always scolding him about not getting his hair cut. To which Johnny always retorted, "Beany, my pigeon, a genius is supposed to be long-haired."

But it was Johnny's smile that set him apart from his fellow men. It wasn't only that it revealed such a perfect set of teeth that the Malone dentist said once he'd like to hire Johnny to sit in his waiting room and smile. His smile had that rare and heart-warming quality of making you one with his plans; it was appealing and gently apologetic. At Harkness High, where Beany was a sophomore and Johnny a senior, other students said it was Johnny's smile, as much as his ability for writing, that melted the grumpiest teacher.

Even Mrs. No-complaint Adams, who gave the Malones the last half of every day to "wash, iron and cook them," was never grim about ten minutes extra if she was ironing Johnny's sport shirts. But then Mrs. Adams was partial to the mentolks in the motherless Malone household. Little Martie she referred to fondly as "the little mister." And as for Martie Malone, father of the Malones! Mrs. Adams was sure that if the president at Washington would just read Martie Malone's editorials in the Morning Call, he would be entirely fit to cope with all the world's problems.

This Saturday noon Mrs. Adams' iron thumped rhythmically in what the family called the butler's pantry though, as Johnny said, no butler had ever sanctified it by his presence. They called their housekeeper Mrs. No-complaint Adams because it was her proud boast that she had "worked out" for seventeen years and had never had a complaint. The next-door neighbor to the south was also a Mrs. Adams. The Malones differentiated by calling her Mrs. Socially-prominent Adams. The society page never misised mentioning one of her teas, luncheons, or committee meetings.

Out on the back porch Elizabeth, Beany's oldest sister, was turning the ice-cream freezer. She came in, her hands clammy and cold from working with ice and salt. "Beany, see if it turns hard enough to take out the dasher. Oh, Beany, warm my hands." Beany chafed them between her warm ones....Oh Elizabeth, Beany thought, I wish I could warm your heart that's so empty and waiting for word from Don...

Elizabeth Malone McCallin was a war bride. It was her three-year-old Martie - the little mister - who was hanging on to Johnny's leg as he reached to a high cupboard shelf for the glass cake plate. Little Martie's hair was three shades lighter than his mother's, and curled about his face like an angel's on a Christmas card. Ever so often the Malone family would gird themselves to get those curls cut off. After all, they didn't want to make a sissy out of him! Once Johnny had even got him as far as Charlie's barber shop on the boulevard. But Johnny brought him back, his fair fluff of curls intact. "Charlie, himself, wasn't there," Johnny excused. "And little Martie and I didn't vibrate to those slap-dash helpers."

Before Elizabeth married she had gone a year to the university. She had been strenuously rushed by ever sorority and pledged by the "prominent" Delts. She had been chosen freshman escort for the Homecoming queen. And, before the year was out, she had been married under crossed swords to Lieutenant Donald McCallin. But now the war was over. Soldiers were returning. But Elizabeth was still waiting for Don to return from overseas.

Elizabeth was lovable and loving - and so lovely! Oh, why couldn't I, Beany often thought, have hair that makes a shining aureole about my face (as they say in books)? Why couldn't boys send me violets and say they were pale compared to my eyes? "Beany is so capable," everyone said... But doggonit, when you were a high-school sophomore and your heart's eyes always followed one certain boy down the hall, it wasn't enough to be tagged as capable...

Johnny found the box with the dozen pink candles and the fullblown rose candle holders. "Good thing Jock isn't thirteen," he said, laying them on the table.

"He's twelve," Beany said, "and he never had a birthday party."

"He'll be here any minute, "Johnny said. "Him and Lorna. Bet they've had Miss Hewlitt up since the break of day."

"I know," Beany laughed, and her spirits lifted. What was more fun than all this making ice cream and cake for a little boy, shunted for safekeeping out of his own country to a rheumatic old uncle Charley? A little boy, who had never had a birthday party and who had been counting the days until this first Saturday in October.

Jock and Lorna were two English children who had been sent over to a great-uncle when England's bombing threatened their safety. The great-uncle was the gardener and handy man for Miss Hewlitt, English Lit teacher at Harkness High and long-time friend of the Malones. In their young loneliness Jock and Lorna had made the Malone home their second home - their preferred home. Never a weekend passed without Jock tagging garrulously after Beany, without Lorna bobbing in and out of the house, paying court with carrots and lettuce leaves to Beany's big white rabbit, Frank. Beany had got in the habit of saving every piece of ribbon to tie on Lorna's hair. Great-uncle Charley or the busy Miss Hewlitt thought a rubber band or piece of string was sufficient to hold a little girl's hair in place.

So Beany vigorously beat the icing until it "formed a peak," visualizing as she did Jock's happy swagger when he saw the cake. Beany's capable fingers slivered off the high part on Johnny's cake and filled in the sunken spot. She slid a newspaper under the cake plate to catch any dripping icing. It was the Morning Call for which her father wrote editorials.

As she iced the cake her eyes noted that the paper was open at one of his sizzling editorials about unfit cars, careless drivers, and the mounting rate of traffic injuries and fatalities. Her knife scooped up a dab of icing off a line that read, "When is our safety maanger, N.J. Rhodes, going to waken from his long nap and do something about this?"

Beany knew an unhappy squirming. It was the irony of fate that her crusading father should be nipping at the heels of the lax N.J. Rhodes while Beany was secretly ordering freckl cream for the benefit of his nephew, Norbett Rhodes, who sat next to her in typing. All other classes at Harkness were just classes - but fith hour her typewriter was next to the one on which Norbett's restless fingers pounded. "What is it two of in occasion - two c's or two s's?" he had asked her. Oh, thank goodness, she could spell! Maybe he hadn't noticed the freckles, or her hair, which Beany, in her pessimistic moments, called "roan." Just yesterday he had asked her, "How would you write the possessive of Haas?"

There, the cake was beautifully iced.

Beany reached for the candle holders and discovered a minor tragedy. Little Martie had chewed on four - no, five - of the rose holders until they resembled worm-eaten rosebuds.

It was always surprising that anyone with as beatific an expression as Little Martie's could get in as much trouble as he did. It was always surprising, too, when little Martie spoke. He didn't talk a baby-talk jumble, but with a slow, feeling-his-way accuracy. "I - like - these," he said slowly, reproachfully, when Beany pried the demolished roses out of his fingers.

Johnny offered to run up to Downey's drugstore for more, but Beany said firmly, "Not you. I'll go." As though Johnny could buy a few candle holders. He'd come back with five dozen. Wasn't Beany still using the pint bottle of almond extract he had bought over three years ago when a recipe had called for a few drops of almond extract?

Beany grabbed Johnny's khaki jacked from the back of a chair and started down the back steps for the drugstore, five blocks away. If the freckle cream was there she'd pick it up, too.

She entered the drugstore breathlessly, with her mind entirely on the candle holders, and hoping that if the icing dripped Johnny would knife it up and put it back onto the cake. Then her heart did a hollow hop, skip, and jump. Norbett Rhodes was standing at the magazine rack, thumbing through a magazine.

Instinctively Beany's two hands reached out and caught her short flappy braids under her combs. Oh, why did she have to meet Norbett Rhodes, wearing this messy plaid seersucker under Johnny's faded, shapeless jacket!

Norbett said, "Hi, Beany!" and she said, "Hi, Norbett!" and stood so he wouldn't see the dab of icing on her skirt.

But the fountain mirror, with its pasted-on patches telling of sundaes and sandwiches, showed a girl with cheeks as pink as the peppermint-stick ice cream that she had mixed earlier. Her eyes weren't the violet blue of Elizabeth's, but a gray-blue shadowed by short but very thick eyelashes. Her "roan" hair hadn't the golden high lights of Elizabeth's, but it had a soap-and-water, a well-brushed shine. Beany's prettiness was of the honest, hardy variety.

The druggist, behind the fountain, called out, "Beany, the freckle cream I ordered for you came. Want to take it?"

"No - no -" she faltered. "I just want some pink candle holders." If only Norbett was too preoccupied with his magazine to notice.

Last year, when Norbett Rhodes was a senior and Beany was in Junior High, she had gone to the Harkness Spring Opera in which Norbett sang the lead. A Viking prince in blue velvet cape with a scarlet lining and a clanking sword, always ready to loose the shackles of the oppressed. Beany, in Harkness parlance, had "fallen on her face" for the senior with his reddish hair, his intense hazel eyes, his stirring Nelson Eddy voice.

She always saw him as cape-and-sword Norbett, even when he sat hunched overh is typewriter until Miss Meigs, their typing teacher, reminded him, "Watch your posture, Norbett." And yet her dream of being Norbett's girl was so hopelessly gummed up. For Beany was realist enough to know that Norbett liked her sister, Mary Fred, and yet disliked Mary Fred because she wouldn't date him. And, even worse, she, Beany, was Martie Malone's daughter. And Martie Malone was viciously berating Norbett's uncle - N.J. Rhodes, safety manager - for his indifferent enforcement of traffic laws. It was this uncle and his wife with whom Norbett madeh is home at the big Park Gate Hotel.

Norbett was still at Harkness High and was vindictively bitter and resentful about being there. Norbett's enemies - and unlike Johnny he had a goodly number - said he had been so busy being a big shot his senior year that he had overshot himself and failed to graduate. Norbett was school reporter for the Tribune, rival paper of Martie Malone's Call. During the winter, when he had covered a ski meet and had been overanxious for a good picture shot, he had climbed a high ledge and slipped and torn a ligament in his ankle. He had missed many chemistry classes because the chem lab was on third floor.

But even so, Norbett was a good enough student, so that all the school was startled when the chemistry professor announced two days before graduation that he was failing Norbett Rhodes. Old stand-pat Professor Bagley! Old Baggy, the students said, thought no boy or girl was equipped to enter the wider realm of life until he or she had mastered the "Nitrogen Cycle."

Norbett opened the heavy drugstore door for Beany, held it against the dusty wind, which promptly ballooned out Beany's jacked and tugged at her braids. "How about a lift home?" he asked. "My wagon's got a new paint job. Shade your eyes when you look at it."

The new paint job was as brightly red as Superman's famous cloak as front-paged on the comic books in the store. "Almost hides all the dents in the fenders," Norbett said, as he swung behind the wheel beside Beany. He asked too casually, "What's Mary Fred doing today?"

"She's going to a Delt tea," Beany said. She thought wretchedly, he' s just taking me home, hoping he'll see Mary Fred - or at least show off the new paint job on his car. ("Old show-off Norbett," Mary Fred always said. "Old hot-stuff himself!")

In the drugstore Norbett had been just a moody, studious, too-thin boy of eighteen or nineteen in a loud sport jacket. But in his red flash of car he took on a reckless, man-about-town swagger. He shot out from the curb. He jabbed a perilous fender-grazing course through the traffic headed for the football game.

"Be careful, Norbett," Beany cried out once, as he barely missed an elderly woman, carrying two bulging sacks of groceries.

"Pedestrians have eyes and legs," he said. "What's to hinder them from being careful?"

"Old people and children can't," she argued.

"Listen at her! Martie Malone's daughter. Brake-and-light Malone, we call him. Impound-the-cars Malone! Him, and his screaming editorials. All the young folks in town would like to strangle him. Old Killjoy Malone! He's slowed traffic on the Boulevard here to twenty-five an hour. What does he want - a funeral procession?"

Beany defended, "He wants to cut down accidents."

Norbett swung onto Barberry street. The white-pillared colonial home of Mrs. Socially-prominent Adams occupied a spacious corner. Its snow-white pillars made its red brick even redder. It had a starched and preening dressiness with its shutters, its ruffled curtains looped back from every window, its window-boxes, brightly splotched now with purple asters. Like a woman dressed for a party in necklace, earrings - even a corsage.

On the far corner was the dark-brick, unadorned home of Judge Buell. Its solid front and massive door had a grim, dignified, even judicial facade. Even the ivy, now a copper red, climbed with watchful decorum up the side. The hedge was squarely trimmed in a "thus far and no farther shalt thou go" manner.

In between sat the wide-bosomed, gray stone Malone home, with its winding driveway at the side. Sitting between these two carefully planned, well-tended homes, the Malone home had neither a starched preeningness nor a grim dignity but rather a scuffed, "come in as you are" friendliness. The Malone barberry hedge, given its own way, was bright with red berries. Their ivy had reached the windows in Father's room and spread protectingly across them.

The mother of the Malones had been the enthusiastic gardener of the family, and though she had been dead give years now, each spring brought glad and surprising remembrances of her. A few little crocuses pushing up in an unexpected corner; a flowering almond bursting into pink glory where they thought bridal wreath held sway. "Mary must have set that out," Father would say. And each time it was like an extra warm smile from her.

Folks driving to the Malone home always whirled into the driveway, for the Malone entrance was on the side, the steps flanked by two sentinel conifer trees. But Norbett Rhodes, as though the Malone driveway was too intimate for a Rhodes, stopped in the street outside with a screech and scream of brakes.

"Well, well," he mocked. "Only two children in the Malone yard!"

"Oh, Jock and Lorna are here already! And the candles aren't on the cake yet!"

"Your place used to look like an orphan asylum when I'd drive past."

Beany said flatly, "Those were the three Biddinger children. Their parents were killed at Pearl Harbor and so Father sent them home to us. They lived with us two years and then - then their uncle down in Santa Fe took them. Marcella - she was just ten when she came -" Beany's flushed face clouded, her voiced choked, "I - missed Marcella - so. Our house seemed so - empty after they left."

Norbett's eyes flicked over the woe in her face. He said, "You Malones certainly stick your neck out for trouble. Didn't you know those orphans from Hawaii wouldn't be with you for keeps? You're a funny kid, Beany. You're so doggoned honest. But you care too much about things. Don't you know there's no percentage in that?"

Beany said impulsively, "Look, Norbett, we've got peppermint-stick ice cream and a birthday cake. I wish you'd come to the party."

He looked at her mockingly. "Don't you know I'm the Malone enemy? All up and down the line. Your father is out tooth and nail after my uncle Norbett. Your sister Mary Fred told me once I had a mean disposition - she said I ought to eat more carrots. And Johnny - well, your genius Johnny and I have always locked horns."

"You mean about all those prize essays and class plays at school?"

"I've never once got the best of Johnny Malone. Last year when I was a senior and he was a junior he always outsmarted me. And this year I've got a swell idea for a senior play, but I suppose if Johnny Malone gets up with some half-baked idea of his, he'll have them all eating out of his hand. I lie awake at night, dreaming of the time when I'll have revenge on the Malones. Shakespeare said a mouthful when he said,

If I can catch him once upon the hip

I will feed fat the ancient grudge I bear him.

Oh yes, and another thing. If you think my uncle Norbett is easy to live with since Martie Malone started nipping at his heels, you're crazy."

What could Beany say? She was tom between loyalty for the Malones and her own secret longing to reach out to him and say, "I'm not your enemy, Norbett."

Norbett said, "I'm covering the football game for the Tribune this aft. How about you dashing out there with me? We can get in on my Press pass. I might need you on the spelling."

Beany's heart lifted high under Johnny's faded jacket. He was asking her. He wasn't thinking of her as Mary Fred's sister. Mentally she was scurrying up the stairs and squirming into her red slipover sweater - and if Mary Fred hadn't worn her navy-blue Chesterfield with the sheepskin lining she'd wear it. Mentally she was feeling Norbett's hand under her elbow, guiding her through the crowded stadium. All the world would see that she was Norbett's girl.

Lorna came to the gate - a little nine-year-old girl with hair that needed Beany's fingers to straighten the part and anchor with a ribbon the curl that was blowing every which way. Lorna said wistfully, proddingly, "Jock says the candles burn on the cake and you blow at them."

Beany reached reluctantly for the car door. "Oh, I'd love to, Norbett, but I - we promised Jock a party. He's never had a party - or a birthday cake -"

"It won't take all afternoon, will it?" Norbett asked impatiently. "It isn't everybody I'd give a second chance to, but I'll telephone you between halves from the Press box. You get this birthday fiddle-faddle off your hands and I'll run down from the stadium and pick you up. Okay?"

"Okay," Beany said.

His red car went careening down Barberry street. Okay? - Beany questioned herself, tremulously and apprehenslvely. Just like playing with fire is okay.

Sample Pages from [em]Behold and See 3: Beginning Science[/em] by Suchi Myjak, illustrated by Cameron Smith

Sample Pages from [em]Beorn the Proud[/em] by Madeleine Polland

THE SUDDEN BREEZE before the dawn stirred the rushes round the island, rocking the small boat which lay among them. In the bottom of the boat a girl moved and woke, confused first at where she found herself. Then she remembered clearly and all the happenings of the previous day came back to her as in a dream of terror. She lay still, looking backwards to the moment yesterday when she had crept happily among these same rushes on the other side of the island. Thigh-deep in water, she had searched for the nests of wildfowl, to surprise her mother with the brown, strong-flavoured eggs which she so valued for the table.

The monastery bell had startled her, clanging violently in the quiet air, but she was not yet frightened—perhaps it was a fire among the island huts or a pack of wolves marauding from the forest by the abbey on the lake shore. Idly, she had parted the tall rushes and peered out between them, only to see great white and scarlet sails spaced all across the lower lake, billowing above long-boats which bore down upon the islands in speed and silence, like huge and brilliant birds of death.

She had not been able to get back to the village in the centre of the island. She had splashed and clawed her way in panic to shallower water, only to realize that the mighty ships were closing even faster than she upon the shore. There had been nothing left to do but hide among the rushes and watch in helplessness as the dark invaders swarmed from their beached ships and poured yelling up the shore to fall upon her father’s village.

Now she could no longer bear her thoughts and sat up abruptly in the boat. Only then did she see the boy, a few feet from her at the water’s edge. He had not seen her and she stared at him in silence; he was one of the invaders and she knew well who they were. She had often heard her father tell of how they had been raiding Ireland now for many years; of how they had come to the homestead when he was a youth in our Lord’s year of 826. That time, however, the people had had warning of their coming and fled to the forests, taking all they could carry, leaving only their crops and homesteads to the pillaging invaders. They came from a far land beyond the sea to the north; the Dubh Gaills they were called. The Black Strangers.

The boy was not tall, but vigorously built, standing braced on his strong brown legs as his eyes followed a flight of duck across the paling sky. She could not see his face but his skin seemed darker than she had ever known, and the hair falling to his shoulders was straight and black. He wore a tunic of grey linen, long-sleeved, and striped with blue and scarlet at the hem. In the leather belt around his waist was the sheath of a long knife.

"But I am not afraid," she told herself. "He is only a boy, about twelve years old like me. He is like one of my brothers."

At the thought of her brothers and the death of her family she stirred again restlessly and this time the boy heard her.

The speed of his movement was like an animal. In one bound he was beside her, reaching for the little wicker boat and drawing it to him through the rushes, staring at her fiercely with wide-open dark-blue eyes.

"Who are you?" he demanded.

She stared at him astonished and did not answer.

"Who are you?" he said again. "My father thought to leave no one alive on these islands. Who are you and how are you here?"

Still she stared at him, amazed green eyes on the demanding blue ones. "But you are a Black Stranger —a Viking," she managed to say at last, "and yet you speak my tongue."

"Yes, yes." The dark face creased with impatience. "My father came on viking here before, and took himself a slave. She reared me when my mother died. My father grew to have much regard for her and we speak your tongue often, my father, my cousin and myself. Also my lord Ragnar and others of the older men have landed here before and passed a winter living among your people. But who are you that I should tell you this! Tell me at once who you are and how you come here. I am Beorn, the Sea King’s son, and I would know."

Life flared back into the frightened and exhausted girl. "And I am Ness, daughter of a chief, and I will tell you only if I please!"

She knelt in the boat, her face only a space away from his, and they glared fiercely, anger risen in them both. Slowly the boy moved his hand to the hilt of the long knife. "I am Beorn," he said again, "the son of Anlaf the Sea King, and you will tell me now!"

Her eyes followed his hand, and then dropped, although her breath still came quick and angry. "Very well, I will tell you."

"It is good," said the boy. He crouched at the bow of the little curragh, never moving while she told him how she had hidden in the rushes and escaped the sacking and burning of the village.

"And then? That was the other side of the island. How did you get here?"

She went on to tell him how she had waited patiently for darkness, almost to her waist in water. Then, when the Vikings had started their feasting on the shore and were gathered rejoicing and unheeding round their fires, she had crept round the island to the little bay on the far side where the curraghs lay in shelter. She had thought to row to the monastery and seek safety with the monks in their tall tower but the Vikings were there before her. It was only the shelter of darkness in a familiar place that had let her escape again to row back, terrified and without thought, to her own island. Here she had lodged the boat deep in the reeds, with no idea of what to do next, and finally in the late night had fallen asleep.

The boy made no comment. He stood up, holding the boat with his foot. "You will get out," he said.

A hot answer rose once more to Ness’s lips, but again the boy laid a casual hand on the long knife, and, her mouth tight with anger, she got out.

As she stood up the boy looked at her. Her tunic was stained and crumpled, her dark-red hair a knotted tangle down to her waist, but her eyes were fierce and her head, he was pleased to find, very nearly as high as his own.

"I like you," he said. "I think you are brave. I will ask my father and you shall be mine."

This time Ness could not hold her temper. "I shall be yours!" she flamed at him. "I shall be yours! I am myself and I shall belong to nobody! Nobody! Least of all to... "

The boy rocked gently on the balls of his feet. The blue eyes mocked her. "Least of all to me," he finished for her. "Very well," he went on, his voice indifferent, "very well. You shall not belong to me. We will tell that to my father Anlaf. Come. Will you then die slowly or quickly, he will surely let me choose? I should say quickly were best. Come. Let us go to my father."

Ness thought of the day before. She thought of the horde of warriors rushing over her father’s almost defenceless village. She heard again the thin, frantic screaming of the women and children, smelt the bitter smell as the smoke and flames rose above the dry thatch of the huts, and heard above everything else the blood-crazy yelling of the plundering Danes. Her anger faded into hopelessness as she looked at the boy—he was only a boy, but he was a Viking like the others.

"I will be yours," she said tonelessly, and for the first time the young Viking smiled.

"It is good. Now come to my father." He set off so suddenly across the short turf that for a brief moment she was alone. She looked at the boat, but before she could think to move he was beside her again. "This is the way to my father." He stood still, close to her, until she turned and went before him along the path which crossed the island.

It was now clear daylight, an early morning in late summer. The small fields above the lake shore had been harvested and the rising sun gilded the stubble above the glitter of the morning lake. In the wood of silver birches in the middle of the island the leaves whispered and rustled with the dryness of the late season. Ness’s steps began to lag.

The boy prodded her from behind. "What?" he said mockingly. "Can you not keep the speed of Viking legs?"

Her chin went up and her steps quickened. She would not tell this hateful boy that she could not bear to see the ruins of her family home on the other side of the wood and, when they passed it, she glanced only once and not again.

The quiet fields above the lake, where her father’s cattle had browsed only yesterday and where the children had wandered down to play around the water, were alive with men. The huge boats, their masts stepped and their striped sails furled, were drawn up on the narrow strip of shore and the morning life of the Vikings was beginning. Aboard the ships some were working. On the shore and in the fields many still slept beside their dead fires, wrapped in their big grey cloaks, the remnants of last night’s feasting still strewn round them. Others sat in groups of three or four round fresh-lit fires, intent on their morning meal.

Numbers of them got up and crowded round the boy and girl as they came out of the wood and down the fields, some laughing, some threatening, all talking noisily. Ness hesitated and drew back nervously. The blue eyes derided her again, but without speaking the boy took her hand in his and led her down the crowded shore until they stood beneath the carved serpent-head which crowned the tall prow of the largest ship.

"What have you there, Beorn? Has one escaped us? Surely you do not come to ask what to do with her?"

The voice, speaking in Ness’s tongue, came from above, and with hardly a glance upwards the boy answered. "You will see, my cousin, both what I have and what I mean to do. Is my father awake?" As he spoke, he scrambled up over the shallow side of the boat, turning to pull Ness after him but without much care, so that she stumbled over the rowers’ benches and fell into a heap in the well of the boat.

There was a loud laugh and the same voice spoke again. "These Irish, they are not people of the sea. Throw her out and let her try again!"

Bruised and resentful, Ness glared upwards. The young man who straddled the high foredeck was tall and broad, handsome, and as fair as Beorn was dark. He laughed uproariously with a couple of men who had drawn close to him, jeering at the girl.

"Throw her back!" the fair young man shouted again to Beorn. "Throw her back and let her try again. That was no way to get into a boat!"

But Beorn dragged her from the well deck and up on to the foredeck, his face dark and angry. "She is mine," he said briefly. "I found her."

"She is yours?" answered the tall one. "Indeed? I would not mind an Irish slave myself, but your father forbade we take them on this raid. Especially I would like one whose hair has tangled with the setting sun. Maybe I will take her." He stretched out a hand and pulled sharply at Ness’s hair.

Beorn jerked her aside, and she glanced from the boy to the fair young man. He still smiled at Beorn, but close to him his face was hard and cruel and there was no smile in his fierce light eyes. The boy’s face was flushed with open hate and he hustled Ness on towards an awning under the curved prow, his flush deepening at the noisy laughter which followed them.

"I will teach him," he muttered. "When I am older, by the great Hammer of Thor, I will show him what it means to be the son of Anlaf!"

But Anlaf the Sea King, when they reached him, was hardly yet awake, and drowsily uninterested in his son’s captive. "Indeed, my son?" He hunched the grey cloak higher around his long form. "You found her? Then you may keep her. What? Oh, pay no heed to your cousin’s teasing. Now leave me. I feasted late and the night watch is not yet over. Go, boy, go, and let me sleep."

For all her sadness and her anger and resentment at being treated like a piece of merchandise, Ness by now was very hungry. When the boy told her to follow him for the morning meal she did so for the first time almost willingly. As they splashed into the shallow water she looked up again and saw the fair young Viking watching them in silence from above.

"I do not like that man," she said. "Who is he?"

The boy glanced sideways at her as if wondering whether he should speak. "He is Helge. I call him cousin, but he is not in truth my cousin, only the son of my father’s foster brother, whom he loved. Helge’s father was killed and Helge driven away, so my father kept him. He is a great fighter, a great Viking and second to my father in command of the fleet, keeping the night watch. He would rule the fleet should anything happen to my father. I am too young to command." His voice was short and resentful. He paused a moment and then burst out: "I do not like him either. I do not trust him. And I do not think my father trusts him; he watches him carefully."

"Why is he so fair, when all the other men are dark or brown?"

"He is no true Dane. He is from Scania, across the water in the country they call Sweden." Beorn remembered suddenly that he was Anlaf’s son and she a captured slave. "I should not talk to you like this! You are my slave, my father said so. Now we shall eat and you shall wait on me."

Ness remembered, too, that she was a chieftain’s daughter. "Wait on you I will not! I am used to having my mother’s servants wait on me. In this country we do not have the meanness of slavery, for we are Christians, and blessed Patrick, who was himself a slave, taught us that no man should own another. And also my father says... said... " Her words and her rage faltered together, and her mouth trembled as she looked piteously across at the ruined village, unable to go on.

The boy watched her a long moment in silence. "A Viking does not drive a woman," he said, then. "Come, we will eat together."

While they ate, the watches changed on the longships. She saw Beorn’s father emerge from the canopy on the Great Serpent, stretching his great length up to the morning sky and shouting for his captains. Never had she seen a man so tall, thin but heavy-shouldered, and moving with the same speed and neatness that marked his son.

The meal over, Ness paused to finger the horn from which she had drunk. She marvelled at the carving on the silver bands which bound it. She had not thought to see barbarians own such a thing of beauty.

The boy got up and left her. "Do not try to run away while I am gone. I have you well watched and you would have no success," he said. "And think, what if Helge caught you!" The blue eyes widened in mockery, and with a laugh at her rising anger he was gone.

She sat on the familiar short turf, where the fields broke on to the lake shore, and tried to think what she might do. She paid no attention to the Vikings, mustering to the ships in their companies for the day’s orders. Her back turned resolutely on her ruined home, she stared down the lake towards the sea. It looked as it had always looked on peaceful summer days; the woods crowding to the edge of the still blue water; the silver birches idling on the small scattered islands and the wildfowl plaintive in the clear air. She was helpless. Her only chance might come at night if she could escape again and reach a boat. Once on the mainland she might be able to find a way through the forests to the fort of her father’s brother, who was a lesser King. A shiver of fear struck her; there were wolves in the forest, sometimes even bears. Defiantly her head went up. Far better wolves and bears than Vikings, she told herself, for she would never belong to any arrogant infuriating Danish boy.

As she brooded, her eyes on the water, she did not notice that the warriors had begun to gather all together on the lake shore. Their talk and laughter roused her in the end and she turned to watch them. They were excited, laughing, shouting and jostling each other round something on the ground. Curiosity made Ness move closer, peering as best she could, for she would not go too close.

For seconds she gazed speechless at what she saw on the ground in the middle of their circle. Then fury took her. She hurled herself screaming through the astonished Vikings, clawing them aside in her blind rage until she stood shaking above the things which they had heaped on the sandy shore.

"You shall not have them!" she screamed. "You shall not have them! They are ours! That was my father’s and this my mother’s! The chalice was the Abbot’s pride... it is priceless! It is not yours! You are thieves, villains, robbers!"

Frantically she struck out at the nearest man, struggling to grab his huge sword from its scabbard. Large hands seized her, and there was laughter above her head and some shouts of anger.

A voice cried, in her tongue: "By the Father of Peoples, my uncle, your son has trapped a wildcat! Take her, Beorn, lest we forget that she is yours—our swords may slip!"

Blind with tears and rage, she allowed the boy to drag her out of the crowd, who at once forgot her, intent on their loot.

Still she beat her fists against Beorn. "It is ours! I saw my mother’s chain of gold, her Cross, it was my father’s precious gift to her! I saw——!"

His strong brown hands grasped her wrists. "Peace, girl, peace! By all the gods, have peace! It is all taken in the raid. It is ours now, each man a share according to his rank. My father is only angry that in their excitement they burned the grain store. This also we would take as is our custom. But on this raid, no slaves, but you."

Anger gave way suddenly in Ness to bitter grief. For the first time since she had seen the great striped sails across the lake she collapsed in desperate knowledge of her loss. She laid her head down upon her knees and sobbed with loneliness and misery. The pathetic heap of goods which the Vikings wrangled over seemed suddenly to stand for all that had been taken—father, mother, five brothers and sisters, her home and all her happy childhood.

"I saw my mother’s Cross," she moaned over and over and over again, never noticing when the boy left her. She sobbed herself at length into an exhausted sleep, worn out with her grief and her long terrifying night.

It was afternoon when she woke, and the soft late sun was creeping westwards towards the sea. Beside her, the boy Beorn sat sharpening his long knife carefully on a stone. She shivered and sat up, aware that the scene before her had changed, but unable to think for a few moments what was different. Then she realized the shore was empty. The great longships were no longer beached. They stood off a little in the water, held by their banks of oars. Only the serpent boat of the Sea King still lay high up upon the shore. She could not help, even in that moment, but see them beautiful; long, narrow and graceful, tapering in perfection to their high sterns and to the carved heads which topped their bows.

She turned to the boy. "What are they doing?"

"They make ready to sail," Beorn answered.

"But where?"

The boy looked at her. "On the next raid. Where else? There is nothing to keep us here. We have eaten your father’s cattle and salted his pigs. We go on to greater treasure now for there was not much here." He breathed lovingly along the gleaming blade of his knife.

Ness stared at him in horror. "And I?"

"You? You will come also. Do you not understand yet that you are mine? You should be proud to belong to Beorn the Sea King’s son. I am proud to be Beorn."

"Well, I am not proud!" she shouted at him. "Not proud! And I will not come to see more of my people slaughtered. You are butchers and robbers and I will not come. I hate you and I will not come!"

Beorn hardly appeared to have heard. He went on sharpening his knife, gazing quietly and critically along the edge of the long blade, brilliant with the light of the setting sun. "Not many will be slaughtered," he said at last, as though it did not much interest him. "Only a few monks. And you will come."

"I will not! I will not!"

"You will come. And you may keep this." Without taking his eyes from his knife, he tossed something at her feet. It was her mother’s chain and Cross.

Dumbly she picked it up and held it, running her fingers over the fine carved links, coming in the end to the Cross itself and its small crowned figure. As long as she could remember her mother, she had fingered it thus, warm about her neck. She looked up at the boy, at a loss for words, too grateful to be angry, and yet still too angry to be properly grateful.

She still had found no words, when, in answer to a signal from his father’s ship, Beorn stood up and sheathed his knife. "You will come," he said.

She slipped the chain over her head and looked in baffled fury at his back. In silence, she followed him.

Sample Pages from [em]Book Title[/em] by Author

Sample Pages from [em]Brightest and Best: Stories of Hymns[/em] by Fr. George Rutler