Sample Card from [em]Lord of History Card Game[/em]

Sample Chapter from The King of the Golden City by Mother Mary Loyola

CHAPTER I

THE MEETING IN THE WOOD

THERE was once a King who lived in a Land where the most lovely flowers bloomed always. His Palace of ivory stood in the midst of a City through which flowed a river clear as crystal. The streets of the City were of pure gold, and the gates were a single pearl each. There was no death nor pain, nor mourn-ing nor crying within those gates, but songs of joy resounded on every side.

Very different from this Land was another which also belonged to the King. It was a country of travelers. Its people were journeying to the Golden City and there were many troubles on the way. The King loved the poor exiles. He tried to keep them safe from harm and to make them happy as far as he could. But to make them quite happy, without any dangers or pain, this he could not do; first, because the country through which they were passing was not meant to be their home, and next because of a certain rebel lord, named Malignus, who lived there. He had once been a servant of the King but had turned against him, and for the hate he bore him, he tried to harm the poor people whom the King loved. The home of the exiles was the Beautiful Land where the King himself lived with all the Happy Ones who had spent their time of exile well and had loved and served their King.

Now it chanced that as the King was wandering one day in a dark wood of the Land of Exile, he came upon a little maid of eight or nine.She was very poor and her clothes, though tidy, were thread-bare. She lived in a hut hard by. Whether it was the King's fancy and nothing more, certain it is that he was drawn to the little maid. He had no sooner seen her than he loved her and longed to make her happy, \ and this at any cost to himself. He spoke kindly to her, took the heavy bundle of faggots off her shoulders, made her sit down by his side on the trunk of a fallen tree, and tell him all about herself and her troubles. When it was time for her to go, he arranged her load so that it was easy for her to carry, and when she turned her head for a last look at him, he was still following her with his kind eyes as if he was sorry to part with her.

After this he would often come to her in the wood, and each time she came to know him better and to love him more. He told her that if she liked, he would take her to his own Beautiful Land where she would be with him always and have everything her heart desired. It could not be at once because she must be trained to be a fit companion for the princes and princesses of the Golden City. But to comfort her till the happy time came, he would of-ten come to see her and he would teach her himself what she would have to learn. In the City everyone was like him: she would have to become like him before she could live amongst them. He would teach her in his visits and would bring her rich presents that she might not be ashamed to be presented at his Court.

One day he gave her a great surprise. He said he was coming to meet her, not in the wood, but in her own little hut, that he might see for himself all she wanted and give her whatever was good for her to have. He spoke so kindly and looked at her so lovingly, that she was sure he meant all he said. Yet she could not help saying:

"How is it, 0 great King, that with so many grand folks and faithful friends about you, you should care to come to a poor little maid like me?"

And he said: "I loved you long before you ever heard of me, and if you will love me in return I shall think myself repaid for all I have done for you and am going to do. You have nothing costly to give me, but there are wild flowers you can offer me. Bring them into your hut and they will please me."

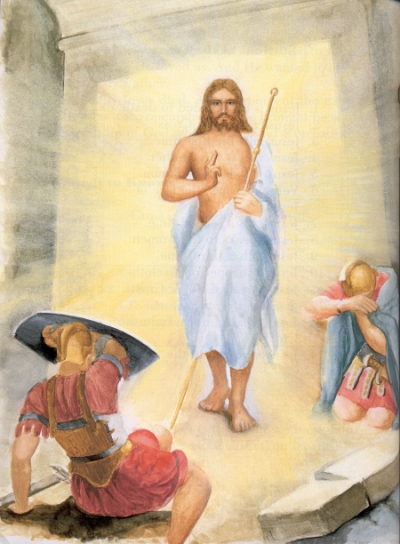

She was delighted and prepared the little place carefully for his coming. The floor was only mud but she swept it clean.She made the one tiny window clear and bright, and drew within a trailing rose that its fragrance might refresh the King. And then she went and hunted diligently for the wild flowers that he loved, the humble violet, the roses with their thorny stems, and, above all, the sweet forget-me-nots. She came home with her apron full. She was tired, for it had cost her something to get her treasures. But she did not mind the trouble if only she could please the King and make him some return for the long journey he would have to take to come to her.She had heard that the treasures he was bring-ing her had not cost him nothing, nay, that he had had to work hard and go through dreadful pain to purchase them. Could she ever do enough for him? He came. Not in all his majesty as he was known in the Golden City, that would only have frightened her, but in a simple robe of white, so dis-guised that some foolish people who knew how great was the King of the Golden City, mocked and said that this meek and lowly stranger could not be he. He came. And you should have seen his smile when he saw the little hut. There was a path through the wood to it all strewn with flowers. At the door the little maid was waiting for him with outstretched arrns. And she brought him into the hut. And the door was shut.

I cannot tell you what passed between them during the quarter of an hour he was within.That is their secret. But when the King came out, the maid's beaming face told what a happy time they had had together. The white robe she had taken care to put on, was all sparkling with jewels - his gifts to her, no doubt. Anyone quite near the door would have heard her say: "Lord, come again soon." She watched him go down the flowery path until it turned and he was out of sight.Then she went in and shut the door, and had anyone been by, he would have heard her singing for days after as she went about her work: "Come, dearest King, again to me, How much, how much I long for thee. "

And he came again, and again. Each time the flowery path was ready, each time the rose trailed through the open pane; each time the forget-me-nots lay about his feet as he and the little maid sat to-gether, hand in nand.

The fifth time -or was it the sixth? - he noticed that the gay path to the hut was shorter, and the flowers less fresh than usual. Perhaps the little maid was tiring of a preparation that must cost something. Anyhow, the King's quick eye noted the change, and a sigh escaped him. Next time he missed the flowers within the hut. He did not complain but his smile was a little sad. After that, his welcome grew less hearty each time he came. He did not get the invitations that were once so pressing, and on the days of his visit the little maid did not fill the place with her song. There was scarcely any preparation for him now. When he came the hut was not dirty, of course, but dusty and uncared for. And he looked in vain for the flowers. He did not change. He brought his rich gifts as usual. But there was no fit spot to lay them down. So he took them away with him, and kept them for the little maid in hopes of better times. And the old times did return. The King came one day as usual - down no flowery pathway now. She was not standing in the doorway but amusing herself within.He had to stoop as he went in, for above and around cobwebs were clinging everywhere.She greeted him, to be sure, and said she was glad to see him, but in a minute or two she got up from her place at his feet and wandered about outside.

Suddenly, a village clock chimed the quarter. It was the time his visits came to a close. And she was not with him! She had left him alone, the friend who had come so far for her sake. The thought of her carelessness and ingratitude rushed upon her. Oh, how could she have been so thoughtless, so unkind! She hurried back to the hut to tell him of her sorrow. But the door was open - he had gone. Gone after such a visit! Oh, what could she do to make it up to him? How different were these last visits from the first in which she had made him so welcome! Could she ever ask him to come again?

Yes, she knew him and she did not despair. Not only would she invite him again, but the welcome should be so hearty as to remind him of their first meeting. She set to work bravely. The hut was scoured and the walls were cleaned. She was tired, but she did not mind - it was for the King. And then, the flowers. She was surprised to find how easily they came to hand. They had not to be fetched from afar, for they lay thick around the hut in every direction and only waited gathering. As to the roses, what if the thorns did prick and make her fingers bleed? They were for the King. She would not mind the pain. And he would know, when he saw them, that she had borne the smart for his sake. Really, when all was ready, the hut looked quite a picture, very poor, of course, but so cared for, so bright. The flowery path was long and gay as on the first glad day. And she longed so to tell him of her sorrow and her love, that it seemed as if the time for his visit would never come. As he crossed the little threshold under the roses, she sank at his feet and her tears fell among the flowers. How ten-derly he raised her, and listened as she told him of her sorrow, and comforted and forgave her! When she asked him what she could do to make up for her carelessness in the past, he said:

"Give me your heart. Love makes up for ev-erything. Love me. Make ready for me in the little ways you know I like. Never mind the trouble and the pain. I have borne pain and trouble for you."

And he showed her great wounds which he told her had been caused by his love for her. She listened, she promised, and because she knew herself to be a little coward, she asked him to help her. And so the old times came back. He was made welcome as before. Not that she was always as careful as she might have been. Oh, no! She was often thoughtless and lazy. But when she had failed, she was sorry and told the King at once.She knew him so well now, and trusted him so fully and was so sure of his love for her that she was not afraid to tell him everything she had done - even the things that were most displeasing to him - since he was with her last. He was always patient with her. He was never tired of forgiving her as soon as she was sorry. He taught her what he wanted her to know so that, gradually, she might grow like him and be made ready for her place in the Golden City.

LESSON ACTIVITIES FOR CHAPTER I

For the full benefit of this allegory, we recommend completing all the Lesson Activities, as age permits.

VOCABULARY

Explain and define each word.

exiles

repaid

preparation

forgiveness

rebel

diligent

ingratitude

patient

companion

meek

comfort

COMPREHENSION

1. What is another name for the Golden City, and what is another name for the Land of Exile?

2. Who is the King?

3. Who is Malignus?

4. Why did Malignus always try to harm the poor people whom the King loved?

5. The King told the little maid that he would take her to the Beautiful Land where she would be with him always.But first she would have to learn to become like someone. Who?

6. Who really is the little maid, and what is her hut?

7. Why does the King want to visit us in Holy Communion, and what is the only thing that he wants from us in return?

8. The flowers that the little maid gathered for the King are like the love and virtues gathered in my heart to receive Jesus in Holy Communion. Did gathering these flowers cost her something, and did she mind?

9. When the King came to the little maid's hut, he was dressed in a simple robe of white so that he would not frighten her. When Jesus Himself comes to us in Holy Communion, what does He look like?