Chapter One

First Years

(1786-1793)

The village of Dardilly is set among the low hills that rise in the neighbourhood of Lyons. One of its inhabitants was Pierre Vianney, husband of Marie Charavay. Besides being a prosperous farmer, he was likewise a man of faith,a nd much given tot he practice of the Christian virtue of charity. In July, 1770, the fame of shig ood works brought to hsi door a mendicant who was also a saint.

Tortured by scruples, Benoit Labre had just left the Trappist monastery of Sept-Fonds, where had been a novice under the name of Brother Urban. He had now acquired a certainty that his vocation was to be a wayfarer for the remainder of his life, so he set out for Rome. His first halt was Paray-le-Monial, where he paid long visits to the chapel fo the Apparitions. From Paray he journeyed to Lyons, but rather than etner the city at nightfall he chose to spend the night at Dardilly. On observing a number of poor persons going to the house of Pierre Vianney, he went along with them.

Benoit Labre was strangely attired. He wore the novice's tunic, which he had been permitted to retain on leaving the monastery. A wallet was suspended from his shoulders, a rosary hung round his neck, and a brass crucifix shone on his breast. A breviary, an Imitation, and the book of the gospels constituted his luggage.

In these weird accoutrements he entered the small enclosure in front of the low-roofed house of the Vianneys. the master of the house received him as he received all destitute persons. The children gazed with pity as the hapless man in whom their parents had taught them to see Jesus Christ himself. Matthieu, one of the five boys, was there. little did he guess. Little did he guess, as he contemplated this youthful mendicant, so pale and so meek, who was telling his beads all the time, that oen day he hismelf would be the father of a saint. In the vast kitchen, near the hearth, where, sixteen years later, the child of predestination would warm his little bare feet, Benoit Labre and his companions in distress sat down with the Vianneys before plates of steaming soup, followed by meat and vegetables. Afer grace and night prayers, the guests were shown a place over the bakehouse, where they were to sleep, and where a thick layer of straw was to be their bed. On the morrow, ere they departed, one and all thanks their hosts, but the refined, gentle youth expressed his gratitude in terms which plainly showed that he was no common beggar.

Great was the surprise of Pierre Vianney when, a little later, he received a letter from the poor pilgrim. Benoit Labre wrote but seldom; the hospitality of Dardilly must have touched him deeply; perhaps God had vouchsafed to give him a presentiment of the child of benediction, who was one day to shed undying lustre upon this house.

Eight years after htis event, on February 11, 1778, at Ecully, a village barely a league from Dardilly, Mattieu Vianney married Marie Beluse. If Matthieu was a good Christian, so also was his young wife, who brought him as the most precious of dowries a keen and enlightened faith.

Their union was blessed by God. They had six children, all of whom, as was the touching customf o the time, were consecrated to our Lady even before their birth. The children's names were: Catherine, who married at an early age and died shortly after her marriage; Jeanne-Marie, who departed to a better world when about five years old; Francois, the heir to the ancestral home; Jean-Marie, now scarcely known by any other name than that of "The Curé of d'Ars"; Marguerite, the only one of the six to survive, and that by several years, her holy brother; lastly, another Francois, called Cadet, who, on joining the army, left Dardilly never again to return.

Jean_Marie was born about midnight on May 8, 1786, and baptized that same day. His godfather and godmother were an uncle and aunt - namely, Jean-Marie Vianney, a younger brother of his father, and his wife Francoise Martinon. The godfather, without looking further afield, was content simply to give his own name to his godson.

So soon as the last comer, a favourite apparently from the start, began to notice things, his mother took pleasure in pointing out to him the crucifix and the pious pictures that adorned the rooms of the farmhouse. When the little arms became strong enough to move with some ease, she guided the tiny hand from teh fore head to the breast and from the breast to the shoulders. The child soon grew into the habit of doing this, so that one day - he was then about fifteen months old - his mother having forgotten to help him to make the sign of the cross before giving him his food, the little one refused to open his mouth, at the same time vigorously shaking his head. Marie Vianney guessed what he meant, and soon as she had helped the tiny hand the pursed-up lips opened spontaneously.

Are we to conclude that even from the cradle Jean-Marie Vianney gave unequivocal proofs of future holiness, such as we read of in the lives of St. Raymond Nonnatus, St. Cajetan, St. Alphonsus Liguori, St. Rose of Lima and so many others? Not one of the existing documents suggests such a phenomenon. However, in all that had to do with religion he was a precocious child, and resopnded much more readily than his brothers and sisters to the solicitude of his admirable mother. His was one of those dispositions that are easily directed towards God. From the age of eighteen months, when the family met for night prayers, he would, of his own accord, kneel down with them - maybe merely from natural imitativeness - and he knew quite well how to join his little hands in prayer.

Prayers ended, his pious mother put h im to bed, and, before a final embrace, she bent over him, talking to him of Jesus, of Mary, of his Guardian Angel. In this way did the fond mother lull the child to sleep.

So soon as he could stand on his feet, he was to be found all over the house, though he did not stray far from the threshold, becuase, on the far side of the yard in the direction of the garden, there was a deep trough where the cattle used to drink. For this reason Jean-Marie hardly ever left his mother's side, busy as she was; on her part, she began the task of her little son's education whilst doing her housework, teaching him in a manner that could be readily grapsed by his cihldish mind. In this way she taught him the "Our Father" and the "Hail Mary" together with some elementary notions of God and of the soul.

The little one, who was very wide awake for his age, woudl himself ask naive questions. What interested him most was the sweet mystery of our Lord's birth at Bethlehem and the story of the manger and the shepherds.

These familiar talks were sometimes prolonged far into the night. For the sake of hearing the story of the Bible, Jean-Marie was willing to sit up late with his mother and Catherine, the most devout of his sisters. Soemtimes he even knelt on the stone floor, folding his hands and putting them within those of his mother.

In fine weather Matthieu Vianney set out very early for the fields, where his wife and the children came to join him in the course of the morning. Catheirne and the elder Francois walked ahead, stick in hand, driving the sheep and cows. A donkey brought up the rear, carrying on his back Jean-Marie and Marguerite, whose pet name was Gothon. On arriving at the fields, the children played on the sward or tended the grazing flock. Jean-Marie was a bright and lively boy, who could put endless zest into their games. Contrary to the assertion of his first biogrpaher, he was very far from being one of those youthful prodigies who have none of the charm and vivacity of their age. This brown-haired, blue-eyed boy, with his pale copmlexion and expressive countenance, did not lack a certain petulance, even though his piety was far in advance of his years. "He was born with an impetuous nature"; his perfect meekness was the fruit of prolonged and meritorious efforts. But from his tenderest years the sensitive and nervous child studied the art of self-conquest. His mother, fully aware of the power of example, often held him up as a pattern to his brothers and sisters; "See," she would say, when they refused to obey promptly, "Jean-Marie is much more obedient than you; he does at once what he is told."

However, once, at least, there were tears. The boy had a rosary which he greatly prized. Gothon, who was eighteen months younger, took a fancy to her brother's beads, and, of course, wished to get possession of them. It came to a scene between brother and sister; there was screaming, stamping of feet, and even a preliminary skirmish, when suddenly, full of grief, the poor child ran to his mother. Gently, but firmly, she bade him give the beads to Gothon: "Yes, my darling, give them to her for the love of the good God." Jean-Marie, though bathed in tears, immediately surrendered his precious rosary. For a child of four this was surely no mean sacrifice! Instead of petting and fondling the child with a view to drying his tears, his mother gaev him a small wooden statue of our Lady. The rude image had long stood on the mantelpiece of the kitchen chimney, and the little one had often wished to possess it. At last it was his, really his! What joy! "Oh! how I loved that statue," he confessed seventy years later; "neither by day nor by night would I be parted from it. I should not have slept had I not had it beside me in my little bed... the Blessed Virgin was the object of my earliest affetions; I loved her even before I knew her."

Some of his contemporaries, his sister Marguerite in particular, have related how, at the first sound of the Angelus, he was on his knees before anybody else. At other times he might be found in a corner of the house kneeling before the image of our Lady, which he had placed on a chair.

Children do not fall victims to the foolish disease called human respect. Wherever he happened to be, whether at home, in the garden, in the street, Jean-Marie, following the exapmle of hsi mother, was in the habit of "blessing the hour," - that is, so soon as he heard the clock strike the hour, he would cross himself and recite a "Hail Mary," ending with another sign of the cross. A neighbour who one day saw him carry out this practice, remarked to Matthieu Vianney: "I believe that little brown-haired fellow of yours takes me for the devil." When Matthieu related the incident, the boy's mother asked him for an explanation: "I did not know our neighbour was looking," was the reply, "but do we not cross ourselves before and after prayers?"

Some women of the neighbourhood, hearing the child praying aloud, said to his parents: "He knows his litanies well. You will have to make him either a priest or a Brother."

Marie Vianney may not have had any inkling of the wonderful future of her favourite child; none the less, the beauty of his soul was precious in her eyes, and she spared no pains to keep from him the very shadow of sin: "See, mon Jean," she used to say, "if your brothers and sisters were to offend the good God, it would indeed cause me much pain, but I should be far sorrier were you to offend him."

Her Jean-Marie was no ordinary child. Even before the powers of his mind had reached their full development, the privileged child of grace had made the first step out of the common way, for this seems to be the true explanation of the following occurrence.

One evening - he was then about four years old - Jean-Marie left the house unnoticed. As soon as his mother became aware of his absence she called to him by his name, but no answer came. With ever-increasing anxiety she looked for him in the yard, behind the straw rick and the piles of timber. The little one was not to be found. Yet he never failed to answer the very first call. As she proceeded in the direction of the stable where he might be hiding, the distracted mother suddenly remembered with horror that deep pond full of murky water, from which the cattle were wont to drink! But what was her surprise when she beheld the spectacle that now presented itself to her eyes? There, in a corner of the stable, among the cattle peacefully chewing the cud, was her boy on his knees, praying with folded hands before his little statue of our Lady. In an instant she had caught him in her arms, and, pressing him to her heart: "Oh! my darling, you were here!" she cried, in a flood of tears. "Why hide yourself when you want to pray? You know we all say our prayers together."

The child, unable to think of anything but his mother's grief, exclaimed: "Forgive me, maman, I did not think; I will not do it again."

Whilst these homely scenes were being enacted in a small and obscure hamlet, events of an appalling nature had taken place in France. However, neither the pillage of Saint-Lazare and the taking of the Bastille (July 13 and 14, 1789) nor the decree depriving the clergy of their benefices (November 2); nor that which suppressed the monasteries and the vows of religion (February 13, 1790), appear to have affected the good country folk: they were either ill-informed or unable to grasp the significance of these events. Hence, their peace of mind was not perturbed until the day when, by the civil constitution of the clergy, the Revolution threatened their priests and their altars (November 26, 1790).

Mme. Vianney was a woman of "eminent piety." If at all possible, she would go to daily Mass. Catherine, her eldest daughter, accompanied her as a rule, but soon her favourite companion came to be the little four-year-old, whose precocious piety caused him to relish the things of God. Whenever the bells of the church near by announced that Mass was about to be said, Jean-Marie entreated his mother to let him go with her. The request was granted. She placed him before her in the family pew, and explained to him what the priest was doing at the altar. The child soon developed a love for the sacred ceremonies. However, his attention was divided: the embroidered vestment of the celebrant entranced him, whilst he was wholly overocme with admiration for the red cassock and white rochet of the altar boy. He, too, would haev liked to serve at the altar, but how could his frail arms lift that heavy Missal? From time to time he turned to his mother; it was an inspiration merely to see her so absorbed in prayer, and as it were transfigured by an interior fire.

In subsequent years, when people congratulated him on his early love for prayer and the Church, he used to say with many tears: "After God, I owe it to my mother; she was so good! Virtue passes readily from the heart of a mother into that of her children. A child that has the happiness of having a good mother should enver look at her or think of her without tears."

First Years

(1786-1793)

The village of Dardilly is set among the low hills that rise in the neighbourhood of Lyons. One of its inhabitants was Pierre Vianney, husband of Marie Charavay. Besides being a prosperous farmer, he was likewise a man of faith,a nd much given tot he practice of the Christian virtue of charity. In July, 1770, the fame of shig ood works brought to hsi door a mendicant who was also a saint.

Tortured by scruples, Benoit Labre had just left the Trappist monastery of Sept-Fonds, where had been a novice under the name of Brother Urban. He had now acquired a certainty that his vocation was to be a wayfarer for the remainder of his life, so he set out for Rome. His first halt was Paray-le-Monial, where he paid long visits to the chapel fo the Apparitions. From Paray he journeyed to Lyons, but rather than etner the city at nightfall he chose to spend the night at Dardilly. On observing a number of poor persons going to the house of Pierre Vianney, he went along with them.

Benoit Labre was strangely attired. He wore the novice's tunic, which he had been permitted to retain on leaving the monastery. A wallet was suspended from his shoulders, a rosary hung round his neck, and a brass crucifix shone on his breast. A breviary, an Imitation, and the book of the gospels constituted his luggage.

In these weird accoutrements he entered the small enclosure in front of the low-roofed house of the Vianneys. the master of the house received him as he received all destitute persons. The children gazed with pity as the hapless man in whom their parents had taught them to see Jesus Christ himself. Matthieu, one of the five boys, was there. little did he guess. Little did he guess, as he contemplated this youthful mendicant, so pale and so meek, who was telling his beads all the time, that oen day he hismelf would be the father of a saint. In the vast kitchen, near the hearth, where, sixteen years later, the child of predestination would warm his little bare feet, Benoit Labre and his companions in distress sat down with the Vianneys before plates of steaming soup, followed by meat and vegetables. Afer grace and night prayers, the guests were shown a place over the bakehouse, where they were to sleep, and where a thick layer of straw was to be their bed. On the morrow, ere they departed, one and all thanks their hosts, but the refined, gentle youth expressed his gratitude in terms which plainly showed that he was no common beggar.

Great was the surprise of Pierre Vianney when, a little later, he received a letter from the poor pilgrim. Benoit Labre wrote but seldom; the hospitality of Dardilly must have touched him deeply; perhaps God had vouchsafed to give him a presentiment of the child of benediction, who was one day to shed undying lustre upon this house.

Eight years after htis event, on February 11, 1778, at Ecully, a village barely a league from Dardilly, Mattieu Vianney married Marie Beluse. If Matthieu was a good Christian, so also was his young wife, who brought him as the most precious of dowries a keen and enlightened faith.

Their union was blessed by God. They had six children, all of whom, as was the touching customf o the time, were consecrated to our Lady even before their birth. The children's names were: Catherine, who married at an early age and died shortly after her marriage; Jeanne-Marie, who departed to a better world when about five years old; Francois, the heir to the ancestral home; Jean-Marie, now scarcely known by any other name than that of "The Curé of d'Ars"; Marguerite, the only one of the six to survive, and that by several years, her holy brother; lastly, another Francois, called Cadet, who, on joining the army, left Dardilly never again to return.

Jean_Marie was born about midnight on May 8, 1786, and baptized that same day. His godfather and godmother were an uncle and aunt - namely, Jean-Marie Vianney, a younger brother of his father, and his wife Francoise Martinon. The godfather, without looking further afield, was content simply to give his own name to his godson.

So soon as the last comer, a favourite apparently from the start, began to notice things, his mother took pleasure in pointing out to him the crucifix and the pious pictures that adorned the rooms of the farmhouse. When the little arms became strong enough to move with some ease, she guided the tiny hand from teh fore head to the breast and from the breast to the shoulders. The child soon grew into the habit of doing this, so that one day - he was then about fifteen months old - his mother having forgotten to help him to make the sign of the cross before giving him his food, the little one refused to open his mouth, at the same time vigorously shaking his head. Marie Vianney guessed what he meant, and soon as she had helped the tiny hand the pursed-up lips opened spontaneously.

Are we to conclude that even from the cradle Jean-Marie Vianney gave unequivocal proofs of future holiness, such as we read of in the lives of St. Raymond Nonnatus, St. Cajetan, St. Alphonsus Liguori, St. Rose of Lima and so many others? Not one of the existing documents suggests such a phenomenon. However, in all that had to do with religion he was a precocious child, and resopnded much more readily than his brothers and sisters to the solicitude of his admirable mother. His was one of those dispositions that are easily directed towards God. From the age of eighteen months, when the family met for night prayers, he would, of his own accord, kneel down with them - maybe merely from natural imitativeness - and he knew quite well how to join his little hands in prayer.

Prayers ended, his pious mother put h im to bed, and, before a final embrace, she bent over him, talking to him of Jesus, of Mary, of his Guardian Angel. In this way did the fond mother lull the child to sleep.

So soon as he could stand on his feet, he was to be found all over the house, though he did not stray far from the threshold, becuase, on the far side of the yard in the direction of the garden, there was a deep trough where the cattle used to drink. For this reason Jean-Marie hardly ever left his mother's side, busy as she was; on her part, she began the task of her little son's education whilst doing her housework, teaching him in a manner that could be readily grapsed by his cihldish mind. In this way she taught him the "Our Father" and the "Hail Mary" together with some elementary notions of God and of the soul.

The little one, who was very wide awake for his age, woudl himself ask naive questions. What interested him most was the sweet mystery of our Lord's birth at Bethlehem and the story of the manger and the shepherds.

These familiar talks were sometimes prolonged far into the night. For the sake of hearing the story of the Bible, Jean-Marie was willing to sit up late with his mother and Catherine, the most devout of his sisters. Soemtimes he even knelt on the stone floor, folding his hands and putting them within those of his mother.

In fine weather Matthieu Vianney set out very early for the fields, where his wife and the children came to join him in the course of the morning. Catheirne and the elder Francois walked ahead, stick in hand, driving the sheep and cows. A donkey brought up the rear, carrying on his back Jean-Marie and Marguerite, whose pet name was Gothon. On arriving at the fields, the children played on the sward or tended the grazing flock. Jean-Marie was a bright and lively boy, who could put endless zest into their games. Contrary to the assertion of his first biogrpaher, he was very far from being one of those youthful prodigies who have none of the charm and vivacity of their age. This brown-haired, blue-eyed boy, with his pale copmlexion and expressive countenance, did not lack a certain petulance, even though his piety was far in advance of his years. "He was born with an impetuous nature"; his perfect meekness was the fruit of prolonged and meritorious efforts. But from his tenderest years the sensitive and nervous child studied the art of self-conquest. His mother, fully aware of the power of example, often held him up as a pattern to his brothers and sisters; "See," she would say, when they refused to obey promptly, "Jean-Marie is much more obedient than you; he does at once what he is told."

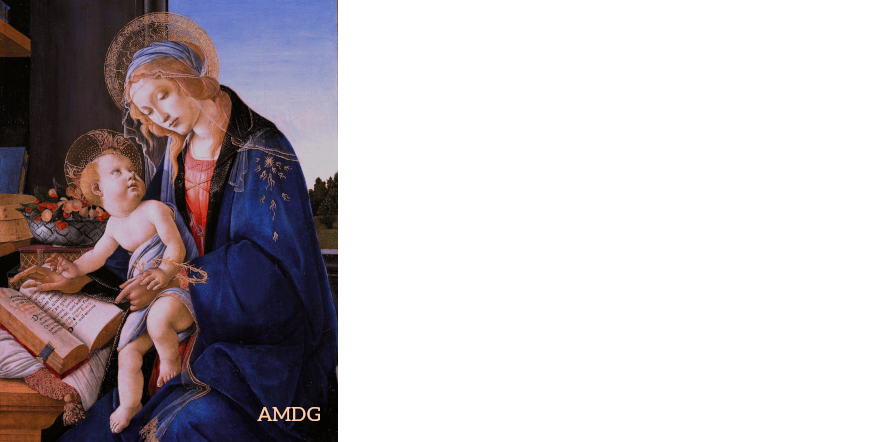

However, once, at least, there were tears. The boy had a rosary which he greatly prized. Gothon, who was eighteen months younger, took a fancy to her brother's beads, and, of course, wished to get possession of them. It came to a scene between brother and sister; there was screaming, stamping of feet, and even a preliminary skirmish, when suddenly, full of grief, the poor child ran to his mother. Gently, but firmly, she bade him give the beads to Gothon: "Yes, my darling, give them to her for the love of the good God." Jean-Marie, though bathed in tears, immediately surrendered his precious rosary. For a child of four this was surely no mean sacrifice! Instead of petting and fondling the child with a view to drying his tears, his mother gaev him a small wooden statue of our Lady. The rude image had long stood on the mantelpiece of the kitchen chimney, and the little one had often wished to possess it. At last it was his, really his! What joy! "Oh! how I loved that statue," he confessed seventy years later; "neither by day nor by night would I be parted from it. I should not have slept had I not had it beside me in my little bed... the Blessed Virgin was the object of my earliest affetions; I loved her even before I knew her."

Some of his contemporaries, his sister Marguerite in particular, have related how, at the first sound of the Angelus, he was on his knees before anybody else. At other times he might be found in a corner of the house kneeling before the image of our Lady, which he had placed on a chair.

Children do not fall victims to the foolish disease called human respect. Wherever he happened to be, whether at home, in the garden, in the street, Jean-Marie, following the exapmle of hsi mother, was in the habit of "blessing the hour," - that is, so soon as he heard the clock strike the hour, he would cross himself and recite a "Hail Mary," ending with another sign of the cross. A neighbour who one day saw him carry out this practice, remarked to Matthieu Vianney: "I believe that little brown-haired fellow of yours takes me for the devil." When Matthieu related the incident, the boy's mother asked him for an explanation: "I did not know our neighbour was looking," was the reply, "but do we not cross ourselves before and after prayers?"

Some women of the neighbourhood, hearing the child praying aloud, said to his parents: "He knows his litanies well. You will have to make him either a priest or a Brother."

Marie Vianney may not have had any inkling of the wonderful future of her favourite child; none the less, the beauty of his soul was precious in her eyes, and she spared no pains to keep from him the very shadow of sin: "See, mon Jean," she used to say, "if your brothers and sisters were to offend the good God, it would indeed cause me much pain, but I should be far sorrier were you to offend him."

Her Jean-Marie was no ordinary child. Even before the powers of his mind had reached their full development, the privileged child of grace had made the first step out of the common way, for this seems to be the true explanation of the following occurrence.

One evening - he was then about four years old - Jean-Marie left the house unnoticed. As soon as his mother became aware of his absence she called to him by his name, but no answer came. With ever-increasing anxiety she looked for him in the yard, behind the straw rick and the piles of timber. The little one was not to be found. Yet he never failed to answer the very first call. As she proceeded in the direction of the stable where he might be hiding, the distracted mother suddenly remembered with horror that deep pond full of murky water, from which the cattle were wont to drink! But what was her surprise when she beheld the spectacle that now presented itself to her eyes? There, in a corner of the stable, among the cattle peacefully chewing the cud, was her boy on his knees, praying with folded hands before his little statue of our Lady. In an instant she had caught him in her arms, and, pressing him to her heart: "Oh! my darling, you were here!" she cried, in a flood of tears. "Why hide yourself when you want to pray? You know we all say our prayers together."

The child, unable to think of anything but his mother's grief, exclaimed: "Forgive me, maman, I did not think; I will not do it again."

Whilst these homely scenes were being enacted in a small and obscure hamlet, events of an appalling nature had taken place in France. However, neither the pillage of Saint-Lazare and the taking of the Bastille (July 13 and 14, 1789) nor the decree depriving the clergy of their benefices (November 2); nor that which suppressed the monasteries and the vows of religion (February 13, 1790), appear to have affected the good country folk: they were either ill-informed or unable to grasp the significance of these events. Hence, their peace of mind was not perturbed until the day when, by the civil constitution of the clergy, the Revolution threatened their priests and their altars (November 26, 1790).

Mme. Vianney was a woman of "eminent piety." If at all possible, she would go to daily Mass. Catherine, her eldest daughter, accompanied her as a rule, but soon her favourite companion came to be the little four-year-old, whose precocious piety caused him to relish the things of God. Whenever the bells of the church near by announced that Mass was about to be said, Jean-Marie entreated his mother to let him go with her. The request was granted. She placed him before her in the family pew, and explained to him what the priest was doing at the altar. The child soon developed a love for the sacred ceremonies. However, his attention was divided: the embroidered vestment of the celebrant entranced him, whilst he was wholly overocme with admiration for the red cassock and white rochet of the altar boy. He, too, would haev liked to serve at the altar, but how could his frail arms lift that heavy Missal? From time to time he turned to his mother; it was an inspiration merely to see her so absorbed in prayer, and as it were transfigured by an interior fire.

In subsequent years, when people congratulated him on his early love for prayer and the Church, he used to say with many tears: "After God, I owe it to my mother; she was so good! Virtue passes readily from the heart of a mother into that of her children. A child that has the happiness of having a good mother should enver look at her or think of her without tears."

Excerpted from The Curé of Ars by Abbé Trochu

Copyright 1927, TAN Books and Publishers, Used with permission.