No name

Faraway Island

So, it just slightly based on the meager accounts of a tale that may have really happened... but still, it makes for a wonderful picture book! Perseverance, kindness, mystery... and true love bringing life to a lonely soul, all in the backdrop of the great navigations involving the Queen of Portugal herself: how can a reader resist it?

Suchi adds: The tale is based on the semi-legendary story of Fernando Lopez, who was a sort of Johnny Appleseed to the island of St. Helena. When he arrived, it was a barren spot in the Atlantic, but over the years, his work transformed it into a lush, beautiful island. Portuguese sailors would stop off there, take what they needed, and leave him grains and plants – even fruit trees – that he would plant and care for.

Father McBride's Teen Catechism

Teen Catechism is a nice entry point into the Catechism of the Catholic Church. In spite of its name, Teen Catechism could be used by an adult convert or any person who wants a solid introduction to or review of our Catholic faith. It follows the topic sequence of the Catechism, covering the Creed, the Sacraments, Morality, and Prayer in its 36 chapters.

Each chapter begins with a passage quoted from another source which is selected as a lead-in to the chapter's topic. The purpose is to raise questions in the reader's mind, or make him aware that there is a question involved. This is followed by a "Some Say" section which is a wrong or incomplete version of the answer. Then there is a "The Catechism Teaches" section which contains quotes from the Catechism on that topic, and "We Catholics Believe" which translates the CCC quotes into everyday language. The "Reflection" is a quote from Scripture or a saint's writings which allows one to meditate further on the topic. Each chapter concludes with "In my Life" a series of open-ended questions which lead the reader to ponder how to apply the stated truths of the chapter to his life. Finally, there is a Prayer and a glossary of theological terms used in the chapter.

The layout is very clear and easy to follow. A variety of fonts are used to distinguish the different parts of the chapter from each other. Brief Scripture verses introduce and conclude the meditations. There is at least one black and white illustration per chapter, either a photograph or a sketch related to the topic. The strategy within the chapters is somewhat similar to St Thomas Aquinas's layout in the Summa Theologicae — a question, some objections, then a reply to the objections. This approach is well suited to the world we live in today, where we often hear a multiplicity of different opinions on a topic, and it is difficult to sort out which is closest to the traditional teachings of the Church.

The book could easily be used in a discussion group, or even as topics for personal devotions. It would be easy to plan "extensions" or further study on a given topic, either by looking into what the Catholic Catechism says in full, or by doing further research on the saints and other people mentioned within the book.

So much of the time, the word "teen" is associated with trendy, lightweight resources, but this book is quite the opposite. It is a solid and thoughtful introduction to the basics of our Catholic faith. One caution for younger readers: in the sections on the 6th and 9th Commandments, the opening stories are of St Maria Goretti, and the story of Susannah and the wicked judges. While the stories are not unnecessarily graphic, they do cover the topic of rape and violence, and may need to be discussed by parents with their younger teenagers.

Fenestrae Fidei

Fenestrae Fidei

I am so excited to post a review on this new coloring book! My girls and I spent a great part of the last weekend working on these beautiful pictures to color! Sean Fitzpatrick, the artist, knows very well what gets young artists to want to grab those colored pencils...

The illustrations are fairly simple for young hands and yet a more experienced artist can have a lot of fun with it. Hillside Education's site offers the suggestion of brushing the finished pictures with vegetable oil for a stained glass effect, and we did that!

Fenestrae Fidei is a companion book to Catholic Mosaic, also by Hillside Education, yet may be perfectly well used alone. For each of the illustrations, which are depicted in calendar (and liturgical) year order, there is a brief explanatory paragraph.

If you want to do it with Catholic Mosaic, a great idea would be to occupy the readers with the coloring activity while the picture book is read aloud. (Catholic Mosaic is a compendium of study/activity guides on numerous Catholic-theme picture books – many of which can be found through your local library).

Fenestrae Fidei (or, in English, "Windows of Faith") comes in a spiral bound format, with a large black & white drawing on each page. There are lots of them, as Catholic Mosaic author Cay Gibson lists four picture books per month. The drawings are all in a stylized iconic style, varying somewhat in intensity of detail. And they are just beautiful!

I would have liked to see a heavier stock paper in the pages, but what we have been doing is scanning and printing copies for home use. This allows for several children, for instance, to work on the same pictures at any time. Hillside Publications allows for coying within one family, which is of course a wonderful advantage.

Fenestrae Fidei is a very Catholic book, reflecting events of the life of Our Lord, the tradition of our Church and the holiness of the saints.

Families today are fortunate to have a product such as this!

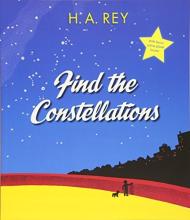

Find the Constellations

I've always loved looking at the stars, but have never been able to identify anything but the big dipper on a starry night. For many years, I've wanted to learn more, but with the busyness of life, this goal has long eluded me. Enter ... Find the Constellations by H.A. Rey. Over the past few weeks, my two oldest children and I have started identifying the constellations with the help of this book and The Stars: A New Way to See Them (by the same author). We've had a great deal of excitement and enthusiasm around 10:00 pm when I summon those children who are still awake to see if we can find anything. With flashlight and books in hand we step outside into the dark. We look up and start to focus. After studying the pictures ahead of time, several constellations start jumping out. We move back and forth between book and sky and the excitement increases. Well, we haven't learned lots yet, but we are now able to identify five or six constellations and are slowly increasing our base knowledge.

This simple book is very child-friendly and moves the reader back and forth between what the stars really look like and simple, memorable stick figures to help keep them (and their names) in our heads. One helpful feature in the carefully drawn charts is the differentiation between brighter and less-bright stars (a very important feature in identification). The book includes some quizzes to help children remember the constellations better and, again, differentiate between the stick-figure drawings and the actual "look" of the constellation. The author also includes: some of the stories behind the naming of the constellations; information about the changes in our sky view at different times of the night and different times of the year; tips for star-gazing; and overviews of the planets in our solar system and tips for viewing them. The book wraps up with some interesting information about what it takes to travel to the moon or to Mars as far as distance, speed and navigation goes. He takes this back to the idea of why it is a good thing to learn the constellations.

All of the information in this book is aimed at viewing the night sky with the naked eye rather than a telescope. There is an extensive index in the back which includes the Latin and Greek names of the constellations (such as Ursa Major and Bootes), but the text uses the English names (except for specific names of stars, such as Vega and Arcturus). The book has been revised numerous times since 1954 and the most recent edition includes location of the planets through 2006. Highly Recommended!

Revised many times since original publication, the book details here are for the 2016 edition.

Finding Darwin's God

This book sat on our bookshelf for quite a while, unread. Honestly, I found the title offputting, especially given Charles Darwin's known rejection of God in his own life. Eventually, my husband read it, and encouraged me to do the same. Dr. Miller says that he was perturbed by what he saw as some Christians' distrust of science, displayed specifically in their rejection of evolutionary theories in favor of creationism or intelligent design. This is a particular concern of Miller, who is himself a Catholic and co-author of the popular "Miller and Levine" high-school biology text. This concern spurred him to write this book defending not only the biological theory of evolution but also the idea that science and religion can be compatible. In the introduction, Miller considers the background and the present situation with regard to these issues both in academia and in the culture at large. I appreciated his honest appraisal of the degree to which "the presumption of atheism or agnosticism is universal in academic life ... how common this presumption of godlessness is." (p. 19) In the following chapter, he explores scientific methods, assumptions, and establishing evidence -- specifically considering areas in which direct experimentation and observation are impossible -- using the analogy of detective work. Following this, he very clearly lays out the case for evolution. He also notes the two distinct ways in which the word "evolution" is used: the first means the natural history of life on earth, characterized by change in time, leading gradually to modern species, while the second refers to the mechanism by which this occurred. Thus, he says, "Evolution is both a fact and a theory." It's important to keep both these meanings in mind. In the next three chapters, Miller successively takes on three well-known ideologies opposed to biological evolution, exploring the religious and scientific flaws of each. First, he takes on young-earth creationism. In a series of arguments from the physical sciences, he lays out a concise and compelling argument for an ancient earth. I was especially impressed with the table of radioactive nuclides and its implications. Then comes the section that explains the chapter's title, "God the Charlatan." Here, Miller provides quotes from a staple of creationist literature (Genesis Flood by Whitcomb and Morris) to the effect that God created a young universe with an "appearance of age." In other words, it's all a hoax. The logical implications of this claim both for science and religion are nothing short of intolerable. In Creator & Creation, Mary Daly draws the same conclusion. Next, he takes on critics such as Philip Johnson, who argue that "micro"-evolution is possible, but not "macro"-evolution. This form of Intelligent Design (ID) argues that evolution can produce minor changes within species, but not new species themselves. Logically, therefore, as Miller observes, God (or the Designer) would have to have created each individual species, including thousands of failed, dead-end species. Further, similar species would have to have been placed geographically and temporally close together and in the right sequences, giving the distinct impression of relatedness where, according to this version of ID, none exists. I appreciated the scientific data that Miller provides in this chapter, as well as his analysis of Eldredge & Gould's "punctuated equilibrium" theory. However, I felt that he equivocated on the term "species" and failed to give a solid definition for it. On p 108, he writes "among bacteria, which is to say among most of the cells alive n the planet, it is particularly easy to see that the differences between species are indeed nothing more than the sum total of differences between their genes." This may indeed be true for bacteria, but among higher species chromosomal differences play a vital role, and no amount of mere gene-level mutations would change chromosomes. I would like to have seen at least some discussion of this. The third criticism of evolution he addresses is the form of ID made popular by biochemist Michael Behe in his book Darwin's Black Box: the claim that certain structures within the cell are "irreducibly complex" and therefore could not have evolved but rather had to be designed. Miller acknowledges that the argument from design is not only the oldest, but the "best rhetorical weapon against evolution." Nevertheless, he argues, it comes up short. As a cell biologist himself, Miller points out that some of Behe's contentions are factually incorrect. For example, although the "9+2" flagellar structure that Behe discusses is the most common, many fully functional flagella and cilia exist that are missing many parts of the supposedly "irreducibly complex" 9+2 structure. He also offers some excellent commentary on the clotting cascade. However, I thought Miller was excessively concerned about the negative impact of ID on research, saying for example, "If you believed Michael Behe's assertion that biochemical machines were irreducibly complex, you might never have bothered to check; and this is the real scientific danger of his ideas." To me this seems highly unlikely, since the nature of science is to test ideas -- even accepted ones. Indeed, Miller himself explains earlier in this book that biologists constantly test evolution knowing that the one who can prove it false will earn instant fame. I do not see why this would not apply equally to ID, were it to ever achieve the level of scientific acceptance that evolution has done. In the next few chapters, Miller discusses the "gods of disbelief" that underpin atheistic materialism, and how these assumptions are contradicted by science itself. He addresses the question of God and evolution. Or, if evolution and other scientific theories explain everything, where does God fit in? His elucidation of the implications of the shift from 19th-century scientific determinism to the 20th century's quantum mechanics is enlightening. In essence, quantum effects mean that science cannot, even in principle, deal in certainties. It can never achieve complete knowledge. Quantum indeterminacy breaks the chain of knowledge and causality and thus, Miller says, it also breaks absolute materialism. He then argues that science and religion are not really contradictory, but complementary. He also provides a fascinating analysis of how the concept of evolution is used (inaccurately) by scientists and intellectuals in support of a worldview hostile to God and religion; this worldview, rather than science itself drives many of the underlying concerns of creationists. The author then looks at some of the findings of cosmology, concentrating on the "anthropic coincidences" of our universe. He argues persuasively that the "traditional explanation" for these -- i.e. God -- is every bit as reasonable as any materialist alternative. Indeed, he suggests, the materialists must be getting a little desperate because they are postulating multiple universes. In this chapter, he also explores the role of chance in life, and what that says (or doesn't say) about God. In the final chapter, Miller ties it all together. I loved the part in which he questions the curious inequity whereby scientific theories can be extrapolated "legitimately" to materialism, atheism, and a non-existence of morality, but never in the opposite direction. Or, as Miller has it: "Apparently it is fine to take a long, hard look at the world and assume scientific authority to say that life has no meaning, but I suspect I would be accused of anti-scientific heresy if I were to do the converse, and claim that on the basis of science I had detected a purpose to existence." (p. 269) He's right on. It is refreshing to see a scientist who not only notices the problem but articulates the double standard so clearly.

Although Miller displays a sound understanding of the scientific facts and their implications, his philosophy and theology seem much weaker. Specifically, I believe he is wrong on the following points:

- He writes, "Given evolution's ability to adapt, to innovate, to test, and to experiment, sooner or later it would have given the Creator exactly what He was looking for -- a creature who, like us, could know Him and love Him, could perceive the heavens and dream of the stars, a creature who would eventually discover the extraordinary process of evolution that filled His earth with so much life." (p. 238-9) It seems to me that he is saying that mind and will -- the abilities to know and love God -- are products of the evolutionary process. But aren't they really powers of the soul, and therefore not evolved in any sense?

- Miller also writes that, "No God [sic] could have created individuals who were free to sin but never chose to do so." (p. 253, emphasis in original) He writes this as part of a paragraph making the point that we are the source of sin, not God. This is an excellent, valid point, but it could easily have been made without the additional (and unwarranted) claim that God could not have made us both free and capable of not sinning. In addition to the exceptional case of Mary, we know that God created angels with free will; some of them chose to sin, while others did not. In fact, Miller's statement is actually self-contradictory, as Dr Rioux explained to me.

- He recounts the tale of Fr. Murphy, who spoke to his First Communion class, saying that, "Flowers, just like you, are the work of God." Years later, at a scientific conference during which a presentation explained how plants make flowers, Miller says, "The real message was, 'Father Murphy, you were wrong.' God doesn't make a flower. The floral induction genes do." (pp. 261-2) I found this particularly jarring given the general thrust of the book that evolution is a means that God created to achieve His purposes. The reality is that God makes flowers by the agency of the floral induction genes. Fr. Murphy was right after all.

- I also thought he weaseled on his belief in God when he wrote (at the end of the book) that he believes in "Darwin's God." This may have been intended as merely a clever retort, but I would have been far more impressed if he had confessed belief in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Or better yet, tied the two together.

Finally, although Miller manages to be commendably charitable through most of his book, I was disappointed with his treatment of a quote from Behe's book to the effect that the "intelligent designer" might be a time traveler (p 162). The quote makes Behe appear to be a bit of a flake, but Miller fails to inform his readers that in this section of his book Behe is exploring ways in which a philosophical naturalist might avoid the implication of a Divine Designer, and toward the end says that: "Most people, like me, will find these scenarios entirely unsatisfactory." (Darwin's Black Box, p 249) Similarly, Miller quotes as Behe's definitive position a passage which is actually preceded in the original work by the words: "Perhaps a speculative scenario will illustrate the point." (ibid, p 227) Nevertheless, I recommend this book to Christians who are interested in getting all the facts in the debate surrounding evolution, creationism, and intelligent design.

Fingal's Quest

The book is originally from the Clarion series, which also includes: If All the Swords in England, Beorn the Proud, Son of Charlemagne and Augustine Came to Kent.

First Communion

Companion to First Confession from Our Lady's Catechists.

In a style very similar to its companion volume, this little book teaches everything that an elementary-school-aged child needs to know to prepare for a holy First Communion. These books may be the first "homeschooling" books ever written on this topic! From page 1: "It should not be forgotten that the ultimate responsibility for the child's spiritual upbringing rests on the parents." Charming full-color illustrations appear throughout the book.

The fourteen lessons describe what Holy Communion is, why we need Holy Communion, and how to prepare to receive Our Lord. In addition, lessons include several Bible stories that provide a gentle apologetic introduction to the Eucharist such as the manna in the desert, miracles performed by Our Lord, and the Last Supper. Prayers for both before and after the reception of Holy Communion are included as well as a "review" question-and-answer page. The lesson titled "On the Day" gives instruction for receiving the Eucharist kneeling and on the tongue, but the general tone of reverence is very applicable for those who receive in the hand. The current one-hour fast rule has been updated in the text from that in practice when originally published.

Imprimatur

Update from webmaster, March 2024: This book and its companion have been republished together in a single volume, First Communion - First Confession. Its ISBN is 9781685290122.

First Communion / First Confession

This is a relatively-recent reprint that combines two older titles by Our Lady's Catechists into a single volume. Please see our individual reviews:

Originally published in 1954. Republished 2022.