No name

Pilgrims of the Holy Family

This program encourages children to learn about themselves and their world while imparting Catholic ideals. Pilgrims of the Holy Family is well suited to be used by individuals or in a group setting as an alternative to secular scouting programs. Written by a homeschooling family of five, "Pilgrims" presents 75 enrichment activities each of which allows the child to achieve a degree of mastery in a particular topic. Those familiar with scouting will recognize some of the topical activity sets as similar to scouting badges. Catholic Heritage Curricula has produced a beautiful set of badges to be awarded at the completion of each topic.

Each topic set is paired with a saint and includes a brief biography along with a list of 5-10 actives that must be done in order for the child to have achieved mastery of that topic. For example "Citizenship" is paired with St. Paul and includes activities such as discussing the difference between loyalty to family, community and the Catholic Church and reporting on five types of government that can be found in history. Topics range from American History and Botany to Reading and Wilderness Survival. Topic areas unique to the Catholic faith include: Catholic Social Thought, Charity, Church History, Missions, Prayer, Virtues, Vocations. There is an appendix at the end of the book that lists appropriate reading material for each of the 75 topic areas.

The authors recommend this program for ages 10 and up. Younger children may find a few topic sets that they can complete, but to perform the work independently the majority of the topics require the cognitive maturity of a child who is at least 10 if not older. We plan on continuing to use this program for after school activities and during summer break throughout high school.

Those interested in support from the authors and others using the program can sign up for the yahoogroups e-mail list.

Pippo the Fool

I heard this story long ago... most certainly from my story-telling aunt, who had the power to do exactly what this phenomenal books does: to turn real life stories into a delightful tale for children! But while my good auntie illustrated her stories with words in a way only she could do, this new publication is illustrated by lines and color in a way that will captivate young and old alike. One would be reminded of Tomie De Paola, but a Tomie de Paola turned-to-life with much more realistic, rich-in-detail full page spreads.

The story is one of big dreams, inventiveness,  and great doses of courage and perseverance. Half a millennium ago in Florence, the great cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore was all built, but for the dome... and a contest was announced for the building of an architectural feat never done before. Little Pippo, called the fool by the people, a goldsmith, dreamed of a plan... and had to undergo quite a bit to accomplish it!

and great doses of courage and perseverance. Half a millennium ago in Florence, the great cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore was all built, but for the dome... and a contest was announced for the building of an architectural feat never done before. Little Pippo, called the fool by the people, a goldsmith, dreamed of a plan... and had to undergo quite a bit to accomplish it!

Pictures books are such integral part of our family life... and books such as Pippo the Fool come to entertain, to educate and to delight. Hats off to writer and illustrator. Do not miss this gem!

Pictures books are such integral part of our family life... and books such as Pippo the Fool come to entertain, to educate and to delight. Hats off to writer and illustrator. Do not miss this gem!

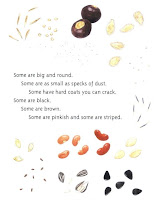

Plant Secrets

I confess I have a stack of books here waiting... some about libraries under different themes. Alas, the warmth today brings our minds to travel towards a green world, full of sunshine and growth.

That, coupled with my 4th grader exclaiming, "Mom, you should blog about this nice book!" has me posting this gem found at the library under new books just yesterday! She is an avid picture book reader and her enthusiasm for this colorful, plant-full book alone is a thumbs up for me!

Product description:

Plants come in all shapes and sizes, but they go through the same stages as they grow. Using four common plants, young readers learn about a plant's life cycles. Simple text and colorful illustrations show the major phases of plant growth: seed, plant, flower, and fruit. Back matter offers more information on each plant, as well as on each stage of growth.

Planting the Trees of Kenya

When I was doing my research for this year's library tree project, I spent a bunch of time at a local bookstore, checking out great new children's titles. Easily my favorite (which it turns out the library had already purchased) was Planting the Trees of Kenya: The Story of Wangari Maathai by Claire A. Nivola.

It's a lovely true story about a lady from Kenya who won the Nobel Peace prize for helping her country recover its economic security by starting a movement to replant the trees and small farms and gardens that had helped the country prosper in the past, but that had been cut down to make way for larger commercial farming (which had devastated the economy).

The thing that had struck me about the book on this first read-through was the beautiful sense of order and dignity - the importance of stewardship of nature, the use of the people themselves as important resources in solving problems, the simplicity of remembering that one person can really make a substantial change, the need for perseverance even when things aren't easy right away. Basically: we change ourselves to change the world. It also has lovely small-is-beautiful and principle-of-subsidiarity sort of themes in it.

The thing I had forgotten was a detail about the years that Wangari had spent in America - where she went to college and majored in biology. I had completely forgotten that she went to a Catholic college (even though the campus picture is portrayed with nuns in habits walking around!). There is a lovely indication in the story that their philosophical influence had a significant impact on her story (and is of course an essential part of the story that her background in biology helped prepare her for her good work):

Her heart was filled with the beauty of her native Kenya when she left to attend a college run by Benedictine nuns in America, far, far from her home. There she studied biology, the science of living things. It was an inspiring time for Wangari. The students in America in those years dreamed of making the world better. The nuns, too, taught Wangari to think not just of herself but of the world beyond herself.

How eagerly she returned to Kenya! How full of hope and of all that she had learned!

The story (and the book) is SO right and so beautiful in so many ways. It's a book anyone could love.

The unexpected discovery I made when I read the "Author's Note" in the back of the book was that the college Wangari attended in the United States was Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas!

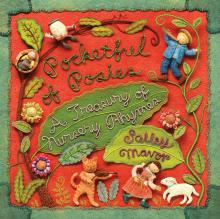

Pocketful of Posies

The entire book was stitched and photographed, and it is one delightful page after another! Enjoy the book's page at the author's website as it offers many inside views plus this series of posts that show a lot of interesting photos on the making of the book, posted by the author!

The nursery rhymes include many old favorites from Mother Goose as well as some less-familiar ones, but it's the illustrations that absolutely steal the show! (Click on the cover image to get an idea.) Author and illustrator Salley Mavor apparently spent a decade developing and honing her trademark fabric relief technique before attempting to illustrate her first book. Each page is crafted from wool felt and sewn and embroidered with multicolored thread, with characters' faces painted on wooden beads. Mavor likes to make furniture and roofs from driftwood bits, and incorporates other found items such as acorn caps and shells into the pictures. She says that each scene takes nearly a month to complete!

The book's primary audience is preschoolers through grade 1 or so, but older children and adults will love the incredible artistry and attention to detail.

Review updated 26 Mar 2024 by Suchi Myjak.

Poetic Knowledge

"There are relatively few persons who can analyze as clearly and as lucidly the writings of Aristotle, Plato, and Aquinas as does this author. Like Taylor's educational philosophy, he seeks to move his readers' affections and will as well as their intellects, and he does this successfully." - Richard Harp, University of Nebraska

When discussing "poetic knowledge" (which is not the knowledge of poetry "but rather a poetic experience of reality"), we are entering into the realm of an intuitive, obscure and somewhat mysterious way of knowing reality that therefor does not lend itself to strict analytical dissection. Nevertheless, in Poetic Knowledge Taylor has managed "with pithy brevity...to provide a history of the treatment of poetic knowledge and to develop his own very persuasive account" – Ralph McInerny (U. of Notre Dame). He cannot reasonably be faulted for failing to make human emotions and intuitions as readily understandable as an isosceles triangle or an elementary rule of grammar - there is more to it than is "dreamt of in our philosophy."

Ironically, it is precisely that relentless demand of modern man (since Descartes) - that all be broken down into parts and pieces for study under a magnifying glass - that Taylor is warning against in his book. A flower loses its beauty when it is hacked into tiny pieces for too close observation; "whatever the sun is, it is not just a mass of burning gasses", though strict analysis might yield just that answer.

Indeed, in writing this book for a modern audience drunk on statistics and mathematical calculation, Taylor assumed the risk of betraying the very thing he was trying to save - the rest of man: his sense, his intuitions, his love of beauty, his integrity and very ability to love. Happily, like a good diagnostic physician,Taylor managed to poke and probe only deeply enough to give us the outlines, to reveal the essentials of the matter without killing the patient in the process.

Like a multi-faceted diamond, poetic knowledge may be viewed from different perspectives, with differing results. Thus it can be considered as both a "degree" of knowledge and as a "mode" of knowledge. As a "mode" of knowledge, poetic knowledge differs from "scientific knowledge" in that is it non-analytical, nor is it about the "outside" of things as observational science is. Rather, it is sensory-emotional, intuitive and deals with the goodness or "inside" of things. It begins with the immediate, direct apprehension of reality that inspires wonder and awe. As a degree of knowledge, it is less certain that mathematical knowledge, but more certain than a mere guess or coin-flip. In short, it is of one certain degree or order, and not of another. A mere review such as this cannot do justice to those distinctions, but that should suffice to account for the fact that Taylor may reasonably approach the matter from different angles without being guilty of the charge of causing needless confusion. No diamond-cutter would do less before striking the blow, and Taylor is writing about more than a mere diamond, he is writing about why women love the beauty and "poetic" meaning of diamond gifts and why men love certain women enough to buy them diamonds.

Taylor makes the point that we live in a world dominated by scientism, by mathematical formulae, which knows the price of all things and the worth of nothing.

He rightly traces this domination back to Descartes, who was a superb mathematician. But Descartes, in promoting his liberal arts of preference - the quadrivium, neglected the rest - the trivium. In stating the obvious - that our world is terribly imbalanced towards the empirical sciences and away from its heart and soul (which is closer to the subject of the trivium) Taylor does us no disservice, nor does he thereby libel the sciences. He is merely trying to restore the balance before science and math bereft of love and beauty calculate us into greater mechanistic slavery or thermonuclear oblivion. One who rights a tottering man ought not be accused of favoring the right over the left, or up over down. Indeed, for left or down to have any meaning, right and up must be preserved as well. Science and math have no future if man has no future. Taylor seeks to restore our future as men and women, not merely as "consumer units" or "human resources".

The Renaissance is a vague term, with a vague start. But out if it did indeed spring modern empirical science as a reaction against the domination of the early Renaissance by rhetorical teachers of the trivium such as Petrarch. Descartes, building on Galileo (1564-1642), and his mathematical arts of the quadrivium, were the ultimate victors in the Renaissance Battle of the Arts, which therefor did triumph - not in the early Renaissance - but in the period of the late Renaissance and Reformation when the trivium and poetic knowledge began to be neglected precisely because of the rise of the quadrivium at that time.

Just as in the late Renaissance, the Battle of the Arts rages and the mathematical sciences still hold the upper hand. They hardly need any more defenders. But like the teacher Keating in the movie Dead Poets Society, Taylor calls us to arms against the tyranny of modern science:

"This is battle...War! And the casualties could be your hearts and your souls...One reads poetry because he is a member of the human race and the human race is filled with passion! Medicine, law, banking - these are necessary to sustain life - but poetry, romance, love, beauty! These are what we stay alive for!"

Restore the balance and the war ends. Then science and faith can indeed be understood harmoniously, but they certainly are not so understood by those in the thrall of modern scientism. In Poetic Knowledge Taylor shows us the way to restore the balance - in the recovery of authentic classical education.

The reviewer is director of the Angelicum Academy Homeschool Program

Poetic Knowledge

However, Taylor's argument is flawed both as a whole and in several of its parts. He resists making clear definitions, he is very negative about science and technology, his historical perspective is distorted, and his writing is problematic.

Resistance to clear definitions is a serious problem. From the start, Taylor speaks of poetic knowledge both as a "degree" of knowledge and as a "mode" of knowledge. By confusing these definitions (and others) Taylor undercuts his central argument with equivocation. As a "degree of knowledge," poetic knowledge is immediate to the knowing person, and may be likened to the lowest rungs of a ladder, the first rungs we climb and the ones we use to climb higher. Understood as a degree of knowledge, poetic knowledge makes a constant contribution to all other forms of knowledge, including scientific knowledge.

As a "mode of knowledge", the poetic is the spontaneous knowledge of an interior view, rather than the measured and outward knowledge of rationality. The poetic as a "mode" of knowledge is the opposite of the "scientific mode". Of course, just as one would be impoverished by looking only east and never west, one would be impoverished if one were to employ only one of two possible modes of knowledge. But they remain opposites.

There are good philosophical reasons and good historical precedents (many of which Taylor produces) for either definition of the term "poetic knowledge," – and even for using both definitions in various ways. But the definitions cannot be interchanged during an argument, and this is what takes place in Taylor's essay. Simply put, his argument is that poetic knowledge (definition 1) is a form of knowledge essential to humanity. But poetic knowledge (definition 2) is the opposite – and the antagonist – of scientific knowledge. By equivocation, poetic knowledge is essential to all knowledge and a powerful human good in opposition to science.

While Taylor does not actually call science an evil, he spares no opportunity to disparage both science and technology. This negativity about science would be comic if it were not encased in an erudite argument for the poetic approach to knowledge in education. Unfortunately, the intuitive and poetic approaches to knowledge are naturally open to romanticism and gnosticism unless they are properly balanced with rationality. Taylor has no balance in this matter. His negativity about rationality overflows even onto sentence diagramming and phonics. He quotes with approval the assertion that "authors teach children to read," and that reading is "imitative". If he merely pointed out that phonics is not enough; you need to have authors that children will enjoy, I would agree. But to scorn phonics? The depth of Taylor's impracticality is simply breathtaking.

A note on history is also in order, for Taylor makes repeated reference to the time of the Reformation and Renaissance, before which the poetic was accepted in Western thought. The correct association for the negative attitude towards intuitive knowledge is the seventeenth century, starting with Descartes, 1596-1650. This is the "Enlightenment" or the "Age of Reason", two names for the time that followed the Renaissance and the Reformation. (Taylor does refer to Descartes as the culprit, but never clarifies his place in history.)

First of all, the Renaissance long preceded the Reformation. It was not a single event, of course, but the starting date sometimes given is 1250, sometimes earlier. Certainly the architectural triumphs of the cathedrals belong to the Renaissance, as do, for example, Dante (1265-1321), Buridan (1300's), Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), and Copernicus (1473-1543). The early Renaissance is the time of the birth of modern science. It predates by hundreds of years the problem that Taylor speaks of. This fact alone should make clear that the rise of science is not the culprit in the loss of respect for poetic knowledge. Something else happened. This is not the place to say what, but only to urge in the strongest terms that no implication against science be received from Taylor's references to the Renaissance.

It may be that Taylor has confused the Renaissance with the Enlightenment. This would explain why he constantly pairs Reformation and Renaissance in the opposite of their historical order, which was Renaissance first, and then later on, the Reformation.

Finally, though it may seem trivial to close on a grammatical note, I shall complain about Taylor's sentence structure. The topic is difficult enough without the distraction of errors of grammar and construction which appear throughout his book. Usually, when a reader is confused about the structure of a sentence, it is his clue that he has not properly followed the author's argument. But in Taylor, it is just a reminder that this author regards analysis as an inferior mode of thought, and wants his argument accepted intuitively.

Because I love science and feed my wonder on the delights of a well-crafted physical argument as much as on violets and poetry, and because I strongly desire that science and faith be understood harmoniously, I cannot recommend this book as a resource for the classical revival in education.

Pope Fiction

This is a wonderful, very readable, book on history and apologetics that takes readers (chronologically) through 30 myths about the papacy and provides very clear answers. The myths cover topics such as: that Peter wasn't really a pope (because he refered to himself as a "fellow presbyter", that the Rock referred to in Matthew 16:10 was not really Peter, that Peter wasn't the ultimate authority in the Church because he was rebuked by St. Paul, that the papacy is merely a medieval Roman invention, that the existence of bad popes disqualifies the papacy as being part of Christ's plan for His Church, that Pope Pius XII was the last validly elected pope (the sedevacantist argument) and that Pope Pius XII was silent in the face of Nazi atrocities against the Jews during World War II.

In the tradition of St. Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica, Patrick Madrid argues against some fairly compelling beliefs of "the other side" in order to help readers more fully understand Catholic doctrine and tradition, as well as be prepared to answer difficult questions posed by non-Catholics and confused Catholics.

Anecdotes and well-chosen quotes really help to illustrate the fallacies of the arguments and make the counter-arguments quite memorable. These responses include quite a bit of pertinent historical details, references to the Bible and the Catechism of the Catholic Church and lots of apologetics "ammunition" for conversations with those who stand against the Pope and the Catholic Church.

Suitable for high school and adult reading.